LETTER VIII

July 11

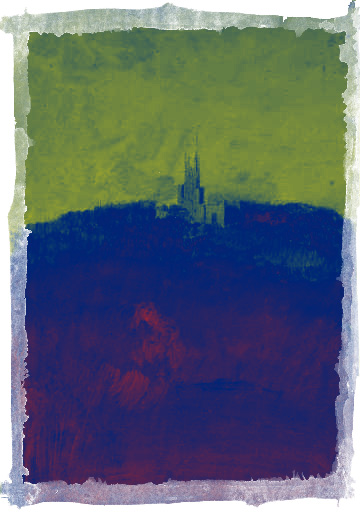

Let those who delight in picturesque country repair to the borders of the Rhine, and follow the road from Bonn to Coblentz. In some places it is suspended like a cornice above the waters; in others, it winds behind lofty steeps and broken acclivities, shaded by woods and clothed with an endless variety of plants and flowers. Several green paths lead amongst this vegetation to the summits of the rocks, which often serve as the foundation of abbeys and castles, whose lofty roofs and spires, rising above the cliffs, impress passengers with ideas of their grandeur, that might probably vanish upon a nearer approach. Not choosing to lose any prejudice in their favour, I kept a respectful distance whenever I left my carriage, and walked on the banks of the river. Just before we came to Andernach, an antiquated town with strange morisco-looking towers, I spied a raft, at least three hundred feet in length, on which ten or twelve cottages were erected, and a great many people employed in sawing wood. The women sat spinning at their doors, whilst their children played among the water-lilies that bloomed in abundance on the edge of the stream. A smoke, rising from one of these aquatic habitations, partially obscured the mountains beyond, and added not a little to their effect. Altogether, the scene was so novel and amusing, that I sat half an hour contemplating it from an eminence under the shade of some leafy walnuts; and should like extremely to build a moveable village, people it with my friends, and so go floating about from island to island, and from one woody coast of the Rhine to another. Would you dislike such a party? I am much deceived, or you would be the first to explore the shades and promontories beneath which we should be wafted along; but I don't think you would find Coblentz, where we were obliged to take up our night's lodging, much to your taste. 'Tis a mean, dirty assemblage of plaistered houses, striped with paint, and set off with wooden galleries, in the beautiful taste of St. Giles's. Above, on a rock, stands the palace of the Elector, which seems to be remarkable for nothing but situation. I did not bestow many looks on this structure whilst ascending the mountain across which our road to Mayence conducted us.

(July 12.) Having attained the summit, we discovered a vast, irregular range of country, and advancing, found ourselves amongst downs, bounded by forests and purpled with thyme. This sort of prospect extending for several leagues, I walked on the turf, and inhaled with avidity the fresh gales that blew over its herbage, till I came to a steep slope overgrown with privet and a variety of luxuriant shrubs in blossom; there, reposing beneath the shade, I gathered flowers, listened to the bees, observed their industry, and idled away a few minutes with great satisfaction. A cloudless sky and bright sunshine made me rather loth to move on, but the charms of the landscape, increasing every instant, drew me forwards. I had not gone far, before a winding valley discovered itself, shut in by rocks and mountains clothed to their very summits with the thickest woods. A broad river, flowing at the base of the cliffs, reflected the impending vegetation, and looked so calm and glassy that I was determined to be better acquainted with it. For this purpose we descended by a zigzag path into the vale, and making the best of our way on the banks of the Lune (for so is the river called) came suddenly upon the town of Emms, famous in mineral story; where, finding very good lodgings, we took up our abode, and led an Indian life amongst the wilds and mountains. After supper I walked on a smooth lawn by the river, to observe the moon journeying through a world of silver clouds that lay dispersed over the face of the heavens. It was a mild genial evening; every mountain cast its broad shadow on the surface of the stream; lights twinkled afar off on the hills; they burnt in silence. All were asleep, except a female figure in white, with glow-worms shining in her hair. She kept moving disconsolately about; sometimes I heard her sigh; and if apparitions sigh, this must have been an apparition. Upon my return, I asked a thousand questions, but could never obtain any information of the figure and its luminaries.

July 13th. The pure air of the morning invited me early to the hills. Hiring a skiff, I rowed about a mile down the stream, and landed on a sloping meadow, level with the waters, and newly mown. Heaps of hay still lay dispersed under the copses which hemmed in on every side this little sequestered paradise. What a spot for a tent! I could encamp here for months, and never be tired. Not a day would pass by without discovering some new promontory, some untrodden pasture, some unsuspected vale, where I might remain among woods and precipices, lost and forgotten. I would give you, and two or three more, the clew of my labyrinth: nobody else should be conscious of its entrance. Full of such agreeable dreams, I rambled about the meads, scarcely knowing which way I was going; sometimes a spangled fly led me astray, and, oftener, my own strange fancies. Between both, I was perfectly bewildered, and should never have found my boat again, had not an old German Naturalist, who was collecting fossils on the cliffs, directed me to it.

When I got home it was growing late, and I now began to perceive that I had taken no refreshment, except the perfume of the hay and a few wood strawberries; airy diet, you will observe, for one not yet received into the realms of Ginnistan*.

July 14th. I have just made a discovery, that this place is as full of idlers and water-drinkers as their Highnesses of Orange and Hesse Darmstadt can desire; for to them accrue all the profits of its salubrious fountains. I protest, I knew nothing of all this yesterday, so entirely was I taken up with the rocks and meadows; and conceived no chance of meeting either card or billiard players in their solitudes. Both abound at Emms, where they hop and fidget from ball to ball, unconscious of the bold scenery in their neighbourhood, and totally insensible to its charms. They had no notion, not they, of admiring barren crags and precipices, where even the Lord would lose his way, as a coarse lubber, decorated with stars and orders, very ingeniously observed to me; nor could they form the least conception of any pleasure there was in climbing like a goat amongst the cliffs, and then diving into woods and recesses where the sun had never penetrated; where there were neither card tables frequented nor sideboards garnished; no jambon de Mayence in waiting; no supply of pipes, nor any of the commonest delights, to be met with in the commonest taverns.

To all this I acquiesced with most perfect submission, but immediately left the orator to entertain a circle of antiquated dames and weather-beaten officers who were gathering around him. Scarcely had I turned my back upon this polite assembly, when Monsieur l'Administrateur des bains, a fine pompous fellow, who had been maitre d'hotel in a great German family, came forward purposely to acquaint me, I suppose, that their baths had the honour of possessing Prince Orloff, "avec sa Grande Maitresse, son Chamberlain, et quelques Dames d'Honneur:" moreover, that his Highness came hither to refresh himself after his laborious employments at the Court of Petersburgh, and expected (grâce aux eaux!) to return to the domains his august sovereign had lately bestowed upon him, in perfect health. Wishing Monsieur d'Orloff all possible success, I should have left the company at a greater distance, had not a violent shower flopped my career, and obliged me to return to my apartment. The rain growing heavier, intercepted the prospect of the mountains, and spread such a gloom over the vale as sunk my spirits fifty degrees; to which a close foggy atmosphere not a little contributed. Towards night the clouds assumed a darker and more formidable aspect. Thunder rolled awfully along the distant cliffs, and several rapid torrents began to run down the steeps. Unable to stay within, I walked into an open portico, listening to the murmur of the river, mingled with the roar of the falling waters. At intervals a blue flash of lightning discovered their agitated surface, and two or three scared women rushing through the storm and calling all the saints in paradise to their assistance. Things were in this state, when the orator who had harangued so brilliantly on the folly of ascending mountains, took shelter under the porch; and, entering immediately into conversation, regaled my ears with a woeful narration of murders which had happened the other day on the precise road I was to follow the next morning. Sir, said he, your route is to be sure very perilous: on the left you have a chasm, down which, should your horses take the smallest alarm, you are infallibly precipitated; to the right hangs an impervious wood, and there, sir, I can assure you, are wolves enough to devour a regiment; a little farther on, you cross a desolate tract of forestland, the roads so deep and broken, that if you go ten paces in as many minutes you may think yourself fortunate. There lurk the most savage banditti in Europe, lately irritated by the Prince of Orange's proscription; and so desperate, that if they make an attack, you can expect no mercy. Should you venture through this hazardous district to-morrow, you will, in all probability, meet a company of people who have just left the town to search for the mangled bodies of their relations; but, for Heaven's sake, sir, if you value your life, do not suffer an idle curiosity to lead you over such dangerous regions, however picturesque their appearance. I own, I felt rather intimidated by so formidable a prospect, and was very near abandoning my plan of crossing the mountains, and so go back again and round about, the Lord knows where; but, considering this step would be quite unheroical, I resolved to attribute my fears to the gloom of the moment, and the dejection it occasioned. It was almost nine o'clock before my kind adviser ceased inspiring me with terrors; then, finding myself at liberty, I retired to bed, not under the most agreeable impressions; and, after tossing and tumbling in the agitation of tumultuous slumbers, I started up at seven in the morning of July 15th, ordered the horses, and set forward, without further dilemmas. Though it had thundered almost the whole night, the air was still clogged with vapours, the mountains bathed in humid clouds, and the scene I had so warmly admired, no longer discernible. Proceeding along the edge of the precipices I had been forewarned of, for about an hour, and escaping that peril at least, we traversed the slopes of a rude, heathy hill, in instantaneous expectation of foes and murderers. A misty rain prevented our seeing above ten yards before us, and every uncouth oak, or rocky fragment, we approached, seemed lurking spies, or gigantic enemies. One time, the murmur of the winds amongst invisible woods of beech, sounded like the wail of distress; and at another the noise of a torrent we could not discover, counterfeited the report of musquetry. In this suspicious manner we journeyed through the forest, which had so recently been the scene of assaults and depredations. At length, after winding several restless hours amongst its dreary avenues, we emerged into open day-light. The sky cleared, a cultivated vale lay before us, and the evening sun, gleaming bright through the vapours, cast a chearful look upon some cornfields, and seemed to promise better times. A few minutes more brought us safe to the village of Viesbaden, where we slept in peace and tranquillity.

July 16. Our apprehensions being entirely dispersed, we rose much refreshed; and passing through Mayence, Oppenheim, and Worms, travelled gaily over the plain in which Manheim is situated. The sun set before we arrived there, and it was by the mild gleams of the rising moon that I first beheld the vast electoral palace, and those long straight streets and neat white houses, which distinguish this elegant capital from almost every other.

Numbers of well-dressed people were amusing themselves with music and fireworks in the squares and open spaces; other groups appeared conversing in circles before their doors, and enjoying the serenity of the evening. Almost every window bloomed with carnations; and we could hardly cross a street without hearing the German flute. A scene of such happiness and retirement contrasted, in the most agreeable manner, with the dismal prospects we had left behind. No storms, no frightful chasms, were here to alarm us; no ruffians, or lawless plunderers; all around was peace, security and contentment in their most engaging attire.

July 17th. Though all impatience to reach that delightful classic region which already possesses, as I have often said, the better half of my spirit, I could not think of leaving Manheim unexplored, and therefore resolved to give up this day to the halls and galleries of the electoral palace. Those, which contain the cabinet of paintings, and sculptures in ivory, form a regular suite of nine immense apartments, about three hundred and seventy-two feet in length, well-proportioned, and uniformly floored with inlaid wood. Each room has ample folding doors, richly gilt and varnished. When seen in perspective, these entrances have the most magnificent effect imaginable. Nothing can give nobler ideas of space than such an enfilade of saloons unincumbered by heavy furniture, where the eyes range without interruption: I wandered alone, from one to the other, and was never wearied with contemplating the variety of pictures which enliven the scene, and convey the highest idea of their collector's taste. When my curiosity was a little satisfied, I left this amusing series of apartments with regret, visited the library, which the present Elector Palatine has formed, upon the same great scale that characterizes his other collections; and, after viewing the rest of the palace, saw the opera-house, which may boast of having contained one of the first bands in Europe: from thence I returned home in a very musical humour. An excellent harpsichord seconded this disposition, which lasted me till late in the evening; when, growing drowsy, I yielded to the influence of sleep, and was in an instant transported to a far more delightful palace than that of the elector; where I expatiated in perfumed apartments with yellow light, and conversed with none but Albano and Claude Lorrain, till the beams of the morning sun entered my chamber, and forced my visiting companions to fly, murmuring to the shades. I cannot say but I was sorry to leave Manheim, though my acquaintance with it was entirely confined to inanimate objects. The cheerful air and free range of the galleries would be sufficient for several days for my amusement; as you know I could people them with phantoms. Not many leagues out of town, lie the famous gardens of Schweidsing. The weather being extremely warm, we were glad to avail ourselves of their shades. There are a great many fountains inclosed by thickets of shrubs and cool alleys, which lead to arbours of trellis-work, festooned with nasturtiums and convolvuluses. Several catalpas and sumachs in full flower, gave considerable richness to the scenery; and whilst we walked amongst them, a fresh breeze gently waved their summits. The tall poplars and acacias, quivering with the air, cast innumerable shadows on the intervening plats of greensward, and, as they moved their branches, discovered other walks beyond, and distant jets of water rising above their foliage, and spangling in the sun. After passing a multitude of shady avenues, terminated by temples, or groups of statues, we followed our guide, through a kind of arched bower, to a little opening in the wood, neatly paved with different-coloured pebbles. On one side, appeared niches and alcoves, ornamented with spars and polished marbles; on the other, an aviary; in front, a superb pavilion, with baths, porticos, and cabinets, fitted up in the most elegant and luxurious style. The song of exotic birds; the freshness of the surrounding verdure heightened by falling streams; and that dubious poetic light admitted through thick foliage, so agreeable after the glare of a sultry day, detained me for some time in an alcove, reading Spenser, and imagining myself but a few paces removed from the Idle Lake. I would fain have loitered an hour more, in this enchanted bower, had not the gardener, whose patience was quite exhausted, and who had never heard of the red-cross knight and his achievements, dragged me away to a sun-burnt, contemptible hillock, commanding the view of a serpentine ditch, and decorated with the title of Jardin Anglois. Some object like decayed lime-kilns and mouldering ovens is disposed in an amphitheatrical form on the declivity of this tremendous eminence: and there is to be seen ivy, and a cascade, and what not, as my conductor observed. A glance was all I bestowed on this caricature upon English gardens; I then went off in a huff at being chased from my bower, and grumbled all the road to Entsweigen; where, to our misfortune, we lay, amidst hogs and vermin, who amply revenged my quarrels with their country.

July 20. After travelling a post or two, we came in sight of a green moor, of vast extent, with many insulated woods and villages; the Danube sweeping majestically along, and the city of Ulm rising upon its banks. The fields in its neighbourhood were overspread with cloths bleaching in the sun, and waiting for barks, which convey them down the great river in ten days to Vienna, and from thence, through Hungary, into the midst of the Turkish empire. I almost envied the merchants their voyage, and, descending to the edge of the stream, preferred my orisons to Father Danube, beseeching him to remember me to the regions through which he flows. I promised him an altar and solemn rites, should he grant my request, and was very idolatrous, till the shadows lengthening over the unlimited plains on his margin, reminded me, that the sun would be shortly sunk, and that I had still above fifteen miles to go. Gathering a purple iris that grew from the bank, I wore it to his honour; and have reason to fancy my piety was rewarded, as not a fly, or an insect, dared to buzz about me the whole evening. You never saw a brighter sky nor more glowing clouds than those which gilded our horizon. The air was impregnated with the perfume of clover, and, for ten miles, we beheld no other objects than smooth levels, enamelled with flowers, and interspersed with thickets of oaks, beyond which appeared a long series of mountains, that distance and the evening tinged with an interesting azure. Such were the very spots for youthful games and exercises, open spaces for tilts, and spreading shades to screen the spectators. Father Lafiteau tells us, there are many such vast and flowery meads in the interior of America, to which the roving tribes of Indians repair once or twice in a century to settle the rights of the chase, and lead their solemn dances; and so deep an impression do these assemblies leave on the minds of the savages, that the highest ideas they entertain of future felicity consist in the perpetual enjoyment of songs and dances upon the green boundless lawns of their elysium. In the midst of these visionary plains rises the abode of Ataentsic, encircled by choirs of departed chieftains leaping in cadence to the mournful sound of spears as they ring on the shell of the tortoise. Their favourite attendants, long separated from them whilst on earth, are restored again in this etherial region, and skim freely over the vast level space; now, hailing one group of beloved friends; and now, another. Mortals, newly ushered by death into this world of pure blue sky and boundless meads, see the long-lost objects of their affection advancing to meet them. Flights of familiar birds, the purveyors of many an earthly chase, once more attend their progress, whilst the shades of their faithful dogs seem coursing each other below. Low murmurs and tinkling sounds, fill the whole region and, as its new denizens proceed, encrease in melody, till, unable to resist the thrilling music, they spring forward in ecctasies to join the eternal round. A share of this celestial transport seemed communicated to me whilst my eyes wandered over the plain, which appeared to widen and extend in proportion as the twilight prevailed. The dusky hour, favorable to conjurations, allowed me to believe the spirits of departed friends not far removed from the clouds, which, to all appearance, reposed at the extremity of the prospect, and tinted the surface of the horizon with ruddy colours. This glow still lingered upon the verge of the landscape, after the sun disappeared; and 'twas in those peaceful moments, when no sound but the browsing of cattle reached me, that I imagined benign looks were cast upon me from the golden vapours, and I seemed to catch glimpses of faint forms moving amongst them, which were once so dear; and even thought my ears affected by well-known voices, long silent upon earth. When the warm hues of the sky were gradually fading, and the distant thickets began to assume a deeper and more melancholy blue, I fancied a shape, like Thisbe*, shot swiftly along; and, sometimes halting afar off, cast an affectionate look upon her old master, that seemed to say, When you draw near the last inevitable hour, and the pale countries of Ataentsic are stretched out before you, I will precede your footsteps, and guide them safe through the wild labyrinths which separate this world from yours. I was so possessed with the ideas, and so full of the remembrance of that poor affectionate creature, whose miserable end you were the witness of, that I did not for several minutes perceive our arrival at Guntsberg. Hurrying to bed, I seemed in my slumbers to pass that interdicted boundary which divides our earth from the region of Indian happiness. Thisbe ran nimbly before me; her white form glimmered amongst dusky forests; she led me into an infinitely spacious plain, where I heard vast multitudes discoursing upon events to come. What further passed must never be revealed. I awoke in tears, and could hardly find spirits enough to look around me, till we were driving through the midst of Augsburg.

July 21st. We dined and rambled about this renowned city in the cool of the evening. The colossal paintings on the walls of almost every considerable building gave it a strange air, which pleases upon the score of novelty. Having passed a number of streets decorated in this exotic manner, we found ourselves suddenly before the public hall, by a noble statue of Augustus, under whose auspices the colony was formed. Which way soever we turned, our eyes met some remarkable edifice, or marble bason into which several groups of sculptured river-gods pour a profusion of waters. These stately fountains and bronze statues, the extraordinary size and loftiness of the buildings, the towers rising in perspective, and the Doric portal of the town-house, answered in some measure the idea Montfaucon gives us of the scene of an ancient tragedy. Whenever a pompous Flemish painter attempts a representation of Troy or Babylon, and displays in his back-ground those streets of palaces described in the Iliad, Augsburg, or some such city, may easily be traced. Sometimes a corner of Antwerp discovers itself; and sometimes, above a Corinthian portico, rises a Gothic spire: just such a jumble may be viewed from the statue of Augustus, under which I remained till the Concierge came, who was to open the gates of the town-house and show me its magnificent hall.

I wished for you exceedingly when, ascending a flight of a hundred steps, I entered it through a portal, supported by tall pillars and crowned with a majestic pediment. Upon advancing, I discovered five more entrances equally grand, with golden figures of guardian genii leaning over the entablature; and saw, through a range of windows, each above thirty feet high, and nearly level with the marble pavement, the whole city, with all its roofs and spires, beneath my feet. The pillars, cornices, and panels of this striking apartment are uniformly tinged with brown and gold; and the ceiling, enriched with emblematical paintings and innumerable canopies of carved work, casts a very magisterial shade. Upon the whole, I should not be surprised at a Burgomaster assuming a formidable dignity in such a room. I must confess it had a similar effect upon me; and I descended the flight of steps with as much pomposity as if a triumphal car waited at my feet, or as if on the point of giving audience to the Queen of Sheba. It happened to be a saint's day, and half the inhabitants of Augsburg were gathered together in the opening before their hall; the greatest numbers, especially the women, still exhibiting the very identical dresses which Hollar engraved. My lofty gait imposed upon this primitive assembly, which receded to give me passage with as much silent respect as if I had really been the wise sovereign of Israel. When I got home, an execrable supper was served up to my majesty; I scolded in an unroyal style, and soon convinced myself I was no longer Solomon.

July 22nd. Joy to the Electors of Bavaria! for planting such extensive woods of fir in their dominions as shade over the chief part of the road from Augsburg to Munich. Near the last-mentioned city, I cannot boast of the scenery changing to advantage. Instead of flourishing woods and verdure, we beheld a parched dreary flat, diversified by fields of withering barley, and stunted avenues drawn formally across them; now and then a stagnant pool, and sometimes a dunghill, by way of regale. However, the wild rocks of the Tirol terminate the view, and to them imagination may fly, and ramble amidst springs and lilies of her own creation. I speak from authority, having had the delight of anticipating an evening in this romantic style. Tuesday next is the grand fair at Munich, with horse-races and junkettings: a piece of news I was but too soon acquainted with; for the moment we entered the town, goodnatured creatures from all quarters advised us to get out of it; since traders and harlequins had filled every corner of the place, and there was not a lodging to be procured. The inns, to be sure, were hives of industrious animals sorting their merchandise, and preparing their goods for sale. Yet, in spite of difficulties, we got possession of a quiet apartment.

July 23rd. We were driven in the evening to Nymphenburg, the Elector's country palace, the bosquets, jets-d'eaux, and parterres of which are the pride of the Bavarians. The principal platform is all of a glitter with gilded Cupids and shining serpents spouting at every pore. Beds of poppies, hollyhocks, scarlet lychnis, and other flame-coloured flowers, border the edge of the walks, which extend till the perspective appears to meet and swarm with ladies and gentlemen in party-coloured raiment. The queen of Golconda's gardens in a French opera are scarcely more gaudy and artificial. Unluckily too, the evening was fine, and the sun so powerful that we were half roasted before we could cross the great avenue and enter the thickets, which barely conceal a very splendid hermitage, where we joined Mr. and Mrs. T., and a party of fashionable Bavarians. Amongst the ladies was Madame la Comtesse, I, forget who, a production of the venerable Haslang, with her daughter, Madame de –, who has the honour of leading the Elector in her chains. These goddesses stepping into a car, vulgarly called a cariole, the mortals followed and explored alley after alley and pavilion after pavilion. Then, having viewed Pagotenburg, which is, as they told me, all Chinese; and Marienburg, which is most assuredly all tinsel; we paraded by a variety of fountains in full squirt, and though they certainly did their best (for many were set agoing on purpose) I cannot say I greatly admired them. The ladies were very gaily attired, and the gentlemen, as smart as swords, bags, and pretty clothes could make them, looked exactly like the fine people one sees represented in a coloured print. Thus we kept walking genteelly about the orangery, till the carriage drew up and conveyed us to Mr. T's. Immediately after supper, we drove once more out of town, to a garden and tea-room, where all degrees and ages dance jovially together till morning. Whilst one party wheel briskly away in the valz, another amuse themselves in a corner with cold meat and rhenish. That despatched, out they whisk amongst the dancers, with an impetuosity and liveliness I little expected to have found in Bavaria. After turning round and round, with a rapidity that is quite astounding to an English dancer, the music changes to a slower movement, and then follows a succession of zig-zag minuets, performed by old and young, straight and crooked, noble and plebeian, all at once, from one end of the room to the other. Tallow candles snuffing and stinking, dishes changing, heads scratching, and all sorts of performances going forward at the same moment; the flutes, oboes, and bassoons, snorting and grunting with peculiar emphasis; now fast, now slow, just as Variety commands, who seems to rule the ceremonial of this motley assembly, where every distinction of rank and privilege is totally forgotten. Once a week, on Sundays that is to say, the rooms are open, and Monday is generally far advanced before they are deserted. If good humour and coarse merriment are all that people desire, here they are to be found in perfection, though at the expense of toes and noses. Both these extremities of my person suffered most cruelly; and I was not sorry to retire, about one in the morning, to a purer atmosphere.

July 24. Custom condemned us to visit the palace, which glares with looking-glass, gilding, and cut velvet. The chapel, though small, is richer than anything Crœsus ever possessed, let them say what they will. Not a corner but shines with gold, diamonds, and scraps of martyrdom studded with jewels. I had the delight of treading amethysts and the richest gems under foot, which, if you recollect, Apuleius thinks such supreme felicity. Alas! I was quite unworthy of the honour, and had much rather have trodden the turf of the mountains. Mammon would never have taken his eyes off the pavement; mine soon left the contemplation of it and fixed on St. Peter's thumb, enshrined with a degree of elegance, and adorned by some malapert enthusiast with several of the most delicate antique cameos I ever beheld; the subjects, Ledas and sleeping Venuses, are a little too pagan, one should think, for an apostle's finger. From this precious repository we were conducted through the public garden to a large hall, where part of the Elector's collection is piled up, till a gallery can be finished for its reception. 'Twas matter of great favour to view, in this state, the pieces that compose it, a very imperfect one too, since some of the best were under operation. But I would not upon any account have missed the sight of Reubens's massacre of the innocents. Such expressive horrors were never yet transferred to canvass, and Moloch himself might have gazed at them with pleasure. After dinner we were led round the churches; and if you are as much tired with reading my voluminous descriptions, as I was with the continual repetition of altars and reliquaries, the Lord have mercy upon you! However, your delivery draws near. The post is going out, and to-morrow we shall begin to mount the cliffs of the Tirol; but, don't be afraid of any long-winded epistles from their summits: I shall be too well employed in ascending them. Just now, as I have lain by a long while, I grow sleek, and scribble on in mere wantonness of spirit. What excesses such a correspondent is capable of, you will soon be able to judge.

July 25th. The noise of the people thronging to the fair did not allow me to slumber very long in the morning. When I got up, every street was crowded with Jews and mountebanks, holding forth and driving their bargains in all the energetic vehemence of the German tongue. Vast quantities of rich merchandise glittered in the shops as we passed along to the gates. Heaps of fruit and sweetmeats set half the grandams and infants in the place a cackling with felicity. Mighty glad was I to make my escape; and in about an hour or two, we entered a wild tract of country, not unlike the skirts of a princely park. A little farther on stands a cluster of cottages, where we stopped to give our horses some refreshment, and were pestered with swarms of flies, most probably journeying to Munich fair, there to feast upon sugared tarts and bottle-noses. The next post brought us over hill and dale, grove and meadow, to a narrow plain, watered by rivulets and surrounded by cliffs, under which lies scattered the village of Wolfrathshausen, consisting of several remarkably large cottages, built entirely of fir, with strange galleries hanging over the way. Nothing can be neater than the carpentry of these simple edifices, nor more solid than their construction; many of them looked as if they had braved the torrents which fell from the mountains a century ago; and, if one may judge from the hoary appearance of the inhabitants, here are patriarchs who remember the Emperor, Lewis of Bavaria. Orchards of cherry-trees impend from the steeps above the village, which to our certain knowledge produce no contemptible fruit; for I can hardly think they eat better in the environs of Damascus. Having refreshed ourselves with their cooling juice, we struck into a grove of pines, the tallest and most flourishing we ever beheld. There seemed no end to these forests, except where little irregular spots of herbage, fed by cattle, intervened. Whenever we gained an eminence it was only to discover more ranges of dark wood, variegated with meadows and glittering streams. White clover and a profusion of sweet-scented flowers clothe their banks; above, waves the mountain-ash, glowing with scarlet berries: and beyond, rise hills, and rocks and mountains, piled upon one another, and fringed with fir to their topmost acclivities. Perhaps the Norwegian forests alone, equal these in grandeur and extent. Those which cover the Swiss highlands rarely convey such vast ideas. There, the woods climb only half way up their ascents, which then are circumscribed by snows: here no boundaries are set to their progress, and the mountains, from base to summit, display rich unbroken masses of vegetation. As we were surveying this prospect, a thick cloud, fraught with thunder, obscured the horizon, whilst flashes of lightning startled our horses, whose snorts and stampings resounded through the woods. What from the shade of the firs and the impending tempests, we travelled several miles almost in total darkness. One moment the clouds began to fleet, and a faint gleam promised serener hours, but the next, all was blackness and terror; presently a deluge of rain poured down upon the valley, and in a short time the torrents beginning to swell, raged with such fury as to be with difficulty forded. Twilight drew on, just as we had passed the most terrible; then ascending a steep hill, whose pines and birches rustled with the storm, we saw a little lake below. A deep azure haze veiled its eastern shore, and lowering vapours concealed the cliffs to the south; but over its western extremities a few transparent clouds, the remains of a struggling sunset, were suspended, which streamed on the surface of the waters, and tinged with tender pink the brow of a verdant promontory. I could not help fixing myself on the banks of the lake for several minutes, till this apparition faded away. Looking round, I shuddered at a craggy mountain, clothed with forests and almost perpendicular, that was absolutely to be surmounted before we could arrive at Wallersee. No house, not even a shed appearing, we were forced to ascend the peak, and penetrate these awful groves. Great praise is due to the directors of the roads across them; which considering their situation, are wonderfully fine. Mounds of stone support the passage in some places; and, in others, it is hewn with incredible labour through the solid rock. Beeches and pines of an hundred feet high, darken the way with their gigantic branches, casting a chill around, and diffusing a woody odour. As we advanced, in the thick shade, amidst the spray of torrents, I could scarcely help thinking myself transported to the Grand Chartreuse; and began to conceive hopes of once more beholding St. Bruno*. But, though that venerable father did not vouchsafe an apparition, or call to me again from the depths of the dells, he protected his votary from nightly perils, and brought us to the banks of Wallersee lake. We saw lights gleam upon its shores, which directed us to a cottage, where we reposed after our toils, and were soon lulled to sleep by the fall of distant waters.

July 26th. The sun rose many hours before me, and when I got up was spangling the surface of the lake, which spreads itself between steeps of wood, crowned by lofty crags and pinnacles. We had an opportunity of contemplating this bold assemblage as we travelled on the banks of the Meer, where it forms a bay sheltered by impending forests; the water, tinged by their reflection with a deep cerulean, calm and tranquil. Mountains of pine and beech rising above, close every outlet; and, no village or spire peeping out of the foliage, impress an idea of more than European solitude. I could contentedly have passed a summer's moon in these retirements; hollowed myself a canoe; and fished for sustenance. From the shore of Wallersee, our road led us straight through arching groves, which the axe seems never to have violated, to the summit of a rock covered with spurge-laurel, and worn by the course of torrents into innumerable craggy forms. Beneath, lay extended a chaos of shattered cliffs, with tall pines springing from their crevices, and rapid streams hurrying between their intermingled trunks and branches. As yet, no hut appeared, no mill, no bridge, no trace of human existence.

After a few hours' journey through the wilderness, we began to discover a wreath of smoke; and presently the cottage from whence it arose, composed of planks, and reared on the very brink of a precipice. Piles of cloven spruce-fir were dispersed before the entrance, on a little spot of verdure browsed by goats; near them sat an aged man with hoary whiskers, his white locks tucked under a fur cap. Two or three beautiful children with hair neatly braided, played around him; and a young woman dressed in a short robe and Polish-looking bonnet, peeped out of a wicket-window. I was so much struck with the exotic appearance of this sequestered family, that, crossing a rivulet, I clambered up to their cottage and begged some refreshment. Immediately there was a contention amongst the children, who should be the first to oblige me. A little black-eyed girl succeeded, and brought me an earthen jug full of milk, with crumbled bread, and a platter of strawberries fresh picked from the bank. I reclined in the midst of my smiling hosts, and spread my repast on the turf: never could I be waited upon with more hospitable grace. The only thing I wanted was language to express my gratitude; and it was this deficiency which made me quit them so soon. The old man seemed visibly concerned at my departure; and his children followed me a long way down the rocks, talking in a dialect which passes all understanding, and waving their hands to bid me adieu. I had hardly lost sight of them and regained the carriage before we entered a forest of pines, to all appearance without bounds, of every age and figure; some, feathered to the ground with flourishing branches; others, decayed into shapes like Lapland idols. I can imagine few situations more dreadful than to be lost at night amidst this confusion of trunks, hollow winds whistling amongst the branches, and strewing their cones below. Even at noonday, I thought we should never have found our way out. At last, having descended a long avenue, endless perspectives opening on either side, we emerged into a valley bounded by swelling hills, divided into agreeable shady inclosures, where many herds were grazing. A rivulet flows along the pastures beneath; and after winding through the village of Boidou, loses itself in a narrow pass amongst the cliffs and precipices which rise above the cultivated slopes and frame in this happy pastoral region. All the plain was in sunshine, the sky blue, the heights illuminated, except one rugged peak with spires of rock, shaped not unlike the views I have seen of Sinai, and wrapped, like that sacred mount, in clouds and darkness. At the base of this tremendous mass lies the hamlet of Mittenvald, surrounded by thickets and banks of verdure, and watered by frequent springs, whose sight and murmurs were so reviving in the midst of a sultry day, that we could not think of leaving their vicinity, but remained at Mittenvald the whole evening. Our inn had long airy galleries, with pleasant balconies fronting the mountain. In one of these we dined upon trout fresh from the rills, and cherries just culled from the orchards that cover the slopes above. The clouds were dispersing, and the topmost peak half visible, before we ended our repast, every moment discovering some inaccessible cliff or summit, shining through the mists, and tinted by the sun with pale golden colours. These appearances filled me with such delight and with such a train of romantic associations, that I left the table and ran to an open field beyond the huts and gardens, to gaze in solitude and catch the vision before it dissolved away. You, if any human being is able, may conceive true ideas of the glowing vapours sailing over the pointed rocks, and brightening them in their passage with amber light. When all were faded and lost in the blue æther, I had time to look around me and notice the mead in which I was standing. Here, clover covered its surface; there, crops of grain; further on, beds of herbs and the sweetest flowers. An amphitheatre of hills and rocks, broken into a variety of dales and precipices, guards the plain from intrusion, and opens a course for several clear rivulets, which, after gurgling amidst loose stones and fragments, fall down the steeps, and are concealed and quieted in the herbage of the vale. A cottage or two peep out of the woods that hang over the waterfalls; and on the brow of the hills above, appears a series of eleven little chapels, uniformly built. I followed the narrow path that leads to them, on the edge of the eminences, and met a troop of beautiful peasants, all of the name of Anna (for it was her saintship's day) going to pay their devotion, severally, at these neat white fanes. There were faces that Guercino would not have disdained copying, with braids of hair the softest and most luxuriant I ever beheld. Some had wreathed it simply with flowers, others with rolls of a thin linen (manufactured in the neighbourhood), and disposed it with a degree of elegance one should not have expected on the cliffs of the Tirol. Being arrived, they knelt all together at the first chapel, on the steps, a minute or two, whispered a short prayer, and then dispersed each to her fane. Every little building had now its fair worshipper, and you may well conceive how much such figures, scattered about the landscape, increased its charms. Notwithstanding the fervour of their adorations (for at intervals they sighed and beat their white bosoms with energy), several bewitching profane glances were cast at me as I passed by. Don't be surprised, then, if I became a convert to idolatry in so amiable a form, and worshipped Saint Anna on the score of her namesakes. When got beyond the last chapel, I began to hear the roar of a cascade in a thick wood of beech and chestnut that clothes the steeps of a wide fissure in the rock. My ear soon guided me to its entrance, which was marked by a shed encompassed with mossy fragments and almost concealed by bushes of the caperplant in full red bloom. Amongst these I struggled, till reaching a goats-track, it conducted me, on the brink of the foaming waters, to the very depths of the cliff, whence issues a stream which, dashing impetuously down, strikes against a ledge of grey rock, and sprinkles the impending thicket with dew. Big drops hung on every spray, and glittered on the leaves partially gilt by the rays of the declining sun, whose mellow hues softened the summits of the cliffs, and diffused a repose, a divine calm, over this deep retirement, which inclined me to imagine it the extremity of the earth, and the portal of some other region of existence; some happy world beyond the dark groves of pine, the caves and awful mountains, where the river takes its source. I hung eagerly on the gulph, impressed with this ideal, and fancied myself listening to a voice that bubbled up with the waters; then looked into the abyss and strained my eyes to penetrate its gloom; but all was dark, and unfathomable as futurity. Awakening from my reverie, I felt the damps of the water chill my forehead, and ran shivering out of the vale to avoid them. A warmer atmosphere, that reigned in the meads I had wandered across before, tempted me to remain a good while longer collecting the wild pinks with which they are strewed in profusion, and a species of thyme scented like myrrh. Whilst I was thus employed, a confused murmur struck my ear, and, on turning towards a cliff, backed by the woods from whence the sound seemed to proceed, forth issued a herd of goats, hundreds after hundreds, skipping down the steeps: then followed two shepherd boys, gamboling together as they drove their creatures along: soon after, the dog made his appearance, hunting a stray heifer which brought up the rear. I followed them with my eyes till lost in the windings of the valley, and heard the tinkling of their bells die gradually away. Now the last blush of crimson left the summit of Sinai, inferior mountains being long since cast in deep blue shades. The village was already hushed when I regained it, and in a few moments I followed its example.

July 27th. We pursued our journey to Inspruck, through the wildest scenes of wood and mountain that were ever traversed, the rocks now beginning to assume a loftier and more majestic appearance, and to glisten with snows. I had proposed passing a day or two at Inspruck, visiting the castle of Ambras, and examining Count Eysenberg's cabinet, enriched with the rarer productions of the mineral kingdom, and a complete collection of the moths and flies peculiar to the Tirol; but, upon my arrival, the azure of the skies and the brightness of the sunshine inspired me with an irresistible wish of hastening to Italy. I was now too near the object of my journey, to delay possession any longer than absolutely necessary; so, casting a transient look on Maximilian's tomb, and the bronze statues of Tirolese Counts and Worthies, solemnly ranged in the church of the Franciscans, set immediately off. We crossed a broad, noble street, terminated by a triumphal arch, and were driven along the road to the foot of a mountain waving with fields of corn, and variegated with wood and vineyards, encircling lawns of the finest verdure, scattered over with white houses, glistening in the sun. Upon ascending the mount, and beholding a vast range of prospects of a similar character, I almost repented my impatience, and looked down with regret upon the cupolas and steeples we were leaving behind. But the rapid succession of lovely and romantic scenes soon effaced the former from my memory. Our road, the smoothest in the world (though hewn in the bosom of rocks) by its sudden turns and windings, gave us, every instant, opportunities of discovering new villages, and forests rising beyond forests; green spots in the midst of wood, high above on the mountains, and cottages perched on the edge of promontories. Down, far below, in the chasm, amidst a confusion of pines and fragments of stone, rages the torrent Inn, which fills the country far and wide with a perpetual murmur. Sometimes we descended to its brink, and crossed over high bridges; sometimes mounted halfway up the cliffs, till its roar and agitation became, through distance, inconsiderable. After a long ascent, the shades of evening reposing in the vallies, and the upland snows still tinged with a vivid red, we reached Schönberg, a village well worthy of its appellation; and then, twilight drawing over us, began to descend. We could now but faintly discover the opposite mountains veined with silver rills, when we came once more to the banks of the Inn. This turbulent stream accompanied us all the way to Steinach, and broke, by its continual roar, the stillness of the night, which had finished half its course, before we were settled to repose.

July 28th. I rose early to scent the fragrance of the vegetation, bathed in a shower which had lately fallen, and looking around me, saw nothing but crags hanging over crags, and the rocky shores of the stream, still dark with the shade of the mountains. The small opening in which Steinach is situated, terminates in a gloomy strait, scarce leaving room for the road and the torrent, which does not understand being thwarted, and will force its way, let the pines grow ever so thick, or the rocks be ever so considerable.

Notwithstanding the forbidding air of this narrow dell, Industry has contrived to enliven its steeps with habitations, to raise water by means of a wheel, and to cover the surface of the rocks with soil. By this means large crops of oats and flax are produced, and most of the huts have gardens adjoining, which are filled with poppies, seeming to thrive in this parched situation:

Urit enim lini campum seges, urit avenæ,

Urunt Lethæo perfusa papavera somno.

The farther we advanced in the dell, the larger were the plantations which discovered themselves. For what purpose these gaudy flowers meet with such encouragement, I had neither time nor language to enquire; the mountaineers stuttering a gibberish unintelligible even to Germans. Probably opium is extracted from them; or, perhaps, if you love a conjecture, Morpheus has transferred his abode from the Cimmerians, and has perceived a cavern somewhere or other in the recesses of these endless mountains. Poppies, you know, in poetic travels, always denote the skirts of his soporific reign, and I don't remember a region better calculated for undisturbed repose than the narrow clefts and gullies which run up amongst these rocks, lost in vapours, impervious to the sun, and moistened by rills and showers, whose continual tricklings inspire a drowsiness not easily to be resisted. Add to these circumstances the waving of the pines, and the hum of bees seeking their food in the crevices, and you will have as sleepy a region as that in which Spenser and Ariosto have placed the nodding deity. At present, I must confess I should not dislike submitting to his empire for a few months or years, just as it might happen, whilst Europe is distracted by dæmons of revenge and war; whilst they are strangling at Venice, and tearing each other to pieces in our unhappy London; whilst Ætna and Vesuvius give signs of uncommon wrath; America welters in her blood; and almost every quarter of the globe is filled with carnage and devastation. This is the moment to humble ourselves before the God of sleep; to beseech him to open his dusky portals, and admit us into the repose of his retired kingdom. If you are inclined to become a suppliant, hasten to the Tirol, and we will search together about the mountains, traverse the poppy-meads, and look into every chasm and fissure that excludes daylight, in hopes of discovering the mansion of repose. Then, when we have found this corner (for I think our search will be successful) Morpheus will give us an approving nod, and beckon us in silence to a couch, where, soon lulled by the murmurs of the place, we shall sink into oblivion and tranquillity. But we may as well keep our eyes open for the present, and look at the beautiful country round Brixen, whither I arrived in the cool of the evening, and breathed the freshness of a garden immediately beneath my window. The thrushes, warbling amongst its shades, saluted me the moment I awoke next morning.

July 29th. We proceeded over fertile mountains to Bolsano. Here, first, I noticed the rocks cut into terraces, thick set with melons and Indian corn; gardens of fig-trees and pomegranates hanging over walls, clustered with fruit; amidst them, a little pleasant cot, shaded by cypresses. In the evening we perceived several further indications of approaching Italy; and after sun-set the Adige, rolling its full tide between precipices, which looked awful in the dusk. Myriads of fire-flies sparkled amongst the shrubs on the bank. I traced the course of these exotic insects by their blue light, now rising to the summits of the trees, now sinking to the ground, and associating with vulgar glow-worms. We had opportunities enough to remark their progress, since we travelled all night; such being my impatience to reach the promised land! Morning dawned just as we saw Trent dimly before us. I slept a few hours, then set out again (July 30th), after the heats were in some degree abated, and leaving Bergine, where the peasants were feasting before their doors in their holiday dresses, with red pinks stuck in their ears instead of rings, and their necks surrounded with coral of the same colour, we came through a woody valley to the banks of a lake, filled with the purest and most transparent water, which loses itself in shady creeks, amongst hills robed with verdure from their base to their summits. The shores present one continual shrubbery, interspersed with knots of larches and slender almonds, starting from the underwood. A cornice of rock runs round the whole, except where the trees descend to the very brink, and dip their boughs in the water. It was six o'clock when I caught the sight of this unsuspected lake, and the evening shadows stretched nearly across it. Gaining a very rapid ascent, we looked down upon its placid bosom, and saw several airy peaks rising above the tufted foliage of the groves around. I quitted the contemplation of them with regret, and, in a few hours, arrived at Borgo di Volsugano, the scenes of the lake still present before the eye of my fancy.

July 31st. My heart beat quick when I saw some hills, not very distant, which I was told lay in the Venetian State, and I thought an age, at least, had elapsed before we were passing their base. The road was never formed to delight an impatient traveller; loose pebbles and rolling stones render it, in the highest degree, tedious and jolting. I should not have spared my execrations, had it not traversed a picturesque valley, overgrown with juniper, and strewed with fragments of rock, precipitated, long since, from the surrounding eminences, blooming with cyclamens. I clambered up several of these crags,

fra gli odoriferi ginepri,

to gather the flowers I have just mentioned, and found them deliciously scented. Fratillarias, and the most gorgeous flies, many of which I here noticed for the first time, were fluttering about and expanding their wings to the sun. There is no describing the numbers I beheld, nor their gaily varied colouring. I could not find in my heart to destroy their felicity; to scatter their bright plumage and snatch them for ever from the realms of light and flowers. Had I been less compassionate, I should have gained credit with that respectable corps, the torturers of butterflies; and might, perhaps, have enriched their cabinets with some unknown captives. However, I left them imbibing the dews of heaven, in free possession of their native rights; and having changed horses at Tremolano, entered at length my long-desired Italy. The pass is rocky and tremendous, guarded by a fortress (Covalo) in possession of the Empress Queen, and only fit, one should think, to be inhabited by her eagles. There is no attaining this exalted hold but by the means of a cord let down many fathoms by the soldiers, who live in dens and caverns, which serve also as arsenals, and magazines for powder; whose mysteries I declined prying into, their approach being a little too aerial for my earthly frame. A black vapour, tinging their entrance, completed the terror of the prospect, which I never shall forget. For two or three leagues it continued much in the same style; cliffs, nearly perpendicular on both sides, and the Brenta foaming and thundering below. Beyond, the rocks began to be mantled with vines and gardens. Here and there a cottage, shaded with mulberries, made its appearance; and we often discovered, on the banks of the river, ranges of white buildings, with courts and awnings, beneath which numbers were employed in manufacturing silk. As we advanced, the stream gradually widened, and the rocks receded; woods were more frequent and cottages thicker strown. About five in the evening we left the country of crags and precipices, of mists and cataracts, and were entering the fertile territory of the Bassanese. It was now I beheld groves of olives, and vines clustering the summits of the tallest elms; pomegranates in every garden, and vases of citron and orange before almost every door. The softness and transparency of the air soon told me I was arrived in happier climates; and I felt sensations of joy and novelty run through my veins, upon beholding this smiling land of groves and verdure stretched out before me. A few glooming vapours, I can hardly call them clouds, rested upon the extremities of the landscape; and, through their medium, the sun cast an oblique and dewy ray. Peasants were returning home, singing as they went, and calling to each other over the hills; whilst the women were milking goats before the wickets of the cottage, and preparing their country fare. I left them enjoying it, and soon beheld the ancient ramparts and cypresses of Bassano; whose classic appearance recalled the memory of former times, and answered exactly the ideas I had pictured to myself of Italian edifices. Though encompassed by walls and turrets, neither soldiers nor custom-house officers start out from their concealments, to question and molest a weary traveller, for such are the blessings of the Venetian state, at least of the Terra Firma provinces, that it does not contain, I believe, above four regiments. Istria, Dalmatia, and the maritime frontiers, are more formidably guarded, as they touch, you know, the whiskers of the Turkish empire. Passing under a Doric gateway, we crossed the chief part of the town in the way to our locanda, pleasantly situated, and commanding a level green, where people walk and eat ices by moonlight. On the right, the Franciscan church, and convent, half hid in the religious gloom of pine and cypress; to the left, a perspective of wall and towers rising from the turf, and marking it, when I arrived, with long shadows; in front, where the lawn terminates, meadow, wood, and garden run quite to the base of the mountains. Twilight coming on, this beautiful spot swarmed with company, sitting in circles upon the grass, refreshing themselves with cooling liquors, or lounging upon the bank beneath the towers. They looked so free and happy that I longed to be acquainted with them; and, by the interposition of a polite Venetian, (who, though a perfect stranger, shewed me the most engaging marks of attention,) was introduced to a group of the principal inhabitants. Our conversation ended in a promise to meet the next evening at a country house about a league from Bassano, and then to return together and sing to the praise of Pachierotti, their idol, as well as mine. You can have no idea what pleasure we mutually found in being of the same faith, and believing in one singer; nor can you imagine what effects that musical divinity produced at Padua, where he performed a few years ago, and threw his audience into such raptures, that it was some time before they recovered. One in particular, a lady of distinction, fainted away the instant she caught the pathetic accents of his voice, and was near dying a martyr to its melody. La Contessa Roberti, who sings in the truest taste, gave me a detail of the whole affair. "Egli ha fatto veramente un fanatismo a Padua," was her expression. I assured her we were not without idolatry in England upon his account; but that in this, as well as in other articles of belief, there were many abominable heretics.

August 1st. The whole morning not a soul stirred who could avoid it. Those who were so active and lively the night before, were now stretched languidly upon their couches. Being to the full as idly disposed, I sat down and wrote some of this dreaming epistle; then feasted upon figs and melons; then got under the shade of the cypress, and slumbered till evening, only waking to dine, and take some ice. The sun declining apace, I hastened to my engagement at Mosolente (for so is the villa called) placed on a verdant hill encircled by others as lovely, and consisting of three light pavilions connected by porticos; just such as we admire in the fairy scenes of an opera. A vast flight of steps leads to the summit, where Signora Roberti and her friends received me with a grace and politeness that can never want a place in my memory. We rambled over all the apartments of this agreeable edifice, characterised by airiness and simplicity. The pavement incrusted with a composition as cool and polished as marble; the windows, doors, and balconies adorned with silvered iron-work, commanding scenes of meads and woodlands that extend to the shores of the Adriatic; spires and cypresses rising above the levels; and the hazy mountains beyond Padua, diversifying the expanse, form altogether a landscape which the elegant imagination of Horizonti never exceeded. Beyond the villa, a tumble of hillocks present themselves in variety of forms, with dips and hollows between, scattered over with leafy trees and vines dangling in continued garlands. I gazed on this rural view till it faded in the dusk; then returning to Bassano, repaired to an illuminated hall, and had the felicity of hearing Signora Roberti sing the very air which had excited such transport at Padua. As soon as she had ended, and that I could hear no more those affecting sounds, which had held me silent and almost breathless for several moments, a band of various instruments, stationed in the open street, began a lively symphony, which would have delighted me at any other time; but now, I wished them a thousand leagues away, so melancholy an impression did the air I had been listening to leave on my mind. At midnight I took leave of my obliging hosts, who were just setting out for Padua. They gave me a thousand kind invitations, and I hope some future day to accept them.

August 2nd. Our route to Venice lay winding about the variegated plains I had surveyed from Mosolente; and after dining at Treviso we came in two hours and a half to Mestre, between grand villas and gardens peopled with statues. Embarking our baggage at the last-mentioned place, we stepped into a gondola, whose even motion was very agreeable after the jolts of a chaise. Stretched beneath the awning, I enjoyed at my ease, the freshness of the gales, and the sight of the waters. We were soon out of the canal of Mestre, terminated by an isle which contains a cell dedicated to the Holy Virgin, peeping out of a thicket, from whence spire up two tall cypresses. Its bells tingled as we passed along and dropped some paolis into a net tied at the end of a pole stretched out to us for that purpose. As soon as we had doubled the cape of this diminutive island, an azure expanse of sea opened to our view, the domes and towers of Venice rising from its bosom.

Now we began to diftinguish Murano, St. Michele, St. Giorgio in Alga, and several other islands, detached from the grand cluster, which I hailed as old acquaintance; innumerable prints and drawings having long since made their shapes familiar. Still gliding forwards, the sun casting his last gleams across the waves, and reddening the distant towers, we every moment distinguished some new church or palace in the city, suffused with the evening rays, and reflected with all their glow of colouring from the surface of the waters. The air was still; the sky cloudless; a faint wind just breathing upon the deep, lightly bore its surface against the steps of a chapel in the island of San Secondo, and waved the veil before its portal, as we rowed by and coasted the walls of its garden overhung with fig-trees and topped with Italian pines. The convent discovers itself through their branches, built in a style somewhat morisco, and level with the sea, except where the garden intervenes. Here, meditation may indulge her reveries in the midst of the surges, and walk in cloisters, alone vocal with the whispers of the pine. I passed this consecrated spot soon after sunset, when daylight was expiring in the west, and when the distant woods of Fusina were lost in the haze of the horizon. We were now drawing very near the city, and a confused hum began to interrupt the evening stillness; gondolas were continually passing and repassing, and the entrance of the canal Reggio, with all its stir and bustle, lay before us. Our gondoliers turned with much address through a crowd of boats and barges that blocked up the way, and rowed smoothly by the side of a broad pavement, covered with people in all dresses and of all nations. Leaving the Palazzo Pesaro, a noble structure with two rows of arcades and a superb rustic, behind, we were soon landed before the Leon Bianco, which being situated in one of the broadest parts of the grand canal, commands a most striking assemblage of buildings. I have no terms to describe the variety of pillars, of pediments, of mouldings, and cornices, some Grecian, others Saracenical, that adorn these edifices, of which the pencil of Canaletti conveys so perfect an idea as to render all verbal description superfluous. At one end of this grand scene of perspective appears the Rialto; the sweep of the canal conceals the other. The rooms of our hotel are as spacious and cheerful as I could desire; a lofty hall, or rather gallery, painted with grotesque in a very good style, perfectly clean, floored with the stucco composition I have mentioned above, divides the house, and admits a refreshing current of air. Several windows near the ceiling look into this vast apartment, which serves in lieu of a court, and is rendered perfectly luminous by a glazed arcade, thrown open to catch the breezes. Through it I passed to a balcony which impends over the canal, and is twined round with plants forming a green festoon springing from two large vases of orange trees placed at each end. Here I established myself to enjoy the cool, and observe, as well as the dusk would permit, the variety of figures shooting by in their gondolas. As night approached, innumerable tapers glimmered through the awnings before the windows. Every boat had its lantern, and the gondolas moving rapidly along were followed by tracks of light, which gleamed and played upon the waters. I was gazing at these dancing fires when the sounds of music were wafted along the canals, and as they grew louder and louder, an illuminated barge, filled with musicians, issued from the Rialto, and stopping under one of the palaces, began a serenade, which stilled every clamour and suspended all conversation in the galleries and porticos; till, rowing slowly away, it was heard no more. The gondoliers catching the air, imitated its cadences, and were answered by others at a distance, whose voices, echoed by the arch of the bridge, acquired a plaintive and interesting tone. I retired to rest, full of the sound; and long after I was asleep, the melody seemed to vibrate in my ear.

August 3rd. It was not five o'clock before I was roused by a loud din of voices and splashing of water under my balcony. Looking out, I beheld the grand canal so entirely covered with fruits and vegetables, on rafts and in barges, that I could scarcely distinguish a wave. Loads of grapes, peaches and melons arrived, and disappeared in an instant, for every vessel was in motion; and the crowds of purchasers hurrying from boat to boat, formed one of the liveliest pictures imaginable. Amongst the multitudes, I remarked a good many whose dress and carriage announced something above the common rank; and upon enquiry I found they were noble Venetians, just come from their casinos, and met to refresh themselves with fruit, before they retired to sleep for the day. Whilst I was observing them, the sun began to colour the balustrades of the palaces, and the pure exhilarating air of the morning drawing me abroad, I procured a gondola, laid in my provision of bread and grapes, and was rowed under the Rialto, down the grand canal to the marble steps of St. Maria della Salute, erected by the Senate in performance of a vow to the Holy Virgin, who begged off a terrible pestilence in 1630. I gazed, delighted with its superb frontispiece and dome, relieved by a clear blue sky. To criticise columns, or pediments of the different façades, would be time lost; since one glance upon the worst view that has been taken of them conveys a far better idea than the most elaborate description. The great bronze portal opened whilst I was standing on the steps which lead to it, and discovered the interior of the dome, where I expatiated in solitude; no mortal appearing except an old priest who trimmed the lamps and muttered a prayer before the high altar, still wrapt in shadows. The sun-beams began to strike against the windows of the cupola, just as I left the church and was wafted across the waves to the spacious platform in front of St. Giorgio Maggiore, by far the most perfect and beautiful edifice my eyes ever beheld. When my first transport was a little subsided, and I had examined the graceful design of each particular ornament, and united the just proportion and grand effect of the whole in my mind, I planted my umbrella on the margin of the sea, and, reclining under its shade, viewed the vast range of palaces, of porticos, of towers, opening on every side and extending out of sight. The Doge's residence and the tall columns at the entrance of the place of St. Mark, form, together with the arcades of the public library, the lofty Campanile and the cupolas of the ducal church, one of the most striking groups of buildings that art can boast of. To behold at one glance these stately fabrics, so illustrious in the records of former ages, before which, in the flourishing times of the republic, so many valiant chiefs and princes have landed, loaded with the spoils of distant nations, was a spectacle I had long and ardently desired. I thought of the days of Frederic Barbarossa, when looking up the piazza of St. Mark, along which he marched in solemn procession, to cast himself at the feet of Alexander the Third, and pay a tardy homage to St. Peter's successor. Here were no longer those splendid fleets that attended his progress; one solitary galeass was all I beheld, anchored opposite the palace of the Doge and surrounded by crowds of gondolas, whose sable hues contrasted strongly with its vermilion oars and shining ornaments. A party-coloured multitude was continually shifting from one side of the piazza to the other; whilst senators and magistrates in long black robes were already arriving to fill their respective charges. I contemplated the busy scene from my peaceful platform, where nothing stirred but aged devotees creeping to their devotions, and, whilst I remained thus calm and tranquil, heard the distant buzz of the town. Fortunately some length of waves rolled between me and its tumults; so that I ate my grapes, and read Metastasio, undisturbed by officiousness or curiosity. When the sun became too powerful, I entered the nef, and applauded the genius of Palladio. After I had admired the masterly structure of the roof and the lightness of its arches, my eyes naturally directed themselves to the pavement of white and ruddy marble, polished, and reflecting like a mirror the columns which rise from it. Over this I walked to a door that admitted me into the principal quadrangle of the convent, surrounded by a cloister supported on Ionic pillars, beautifully proportioned. A flight of stairs opens into the court, adorned with balustrades and pedestals, sculptured with an elegance truly Grecian. This brought me to the refectory, where the chef d'oeuvre of Paul Veronese, representing the marriage of Cana in Galilee, was the first object that presented itself. I never beheld so gorgeous a group of wedding-garments before; there is every variety of fold and plait that can possibly be imagined. The attitudes and countenances are more uniform, and the guests appear a very genteel, decent sort of people, well used to the mode of their times and accustomed to miracles. Having examined this fictitious repast, I cast a look on a long range of tables covered with very excellent realities, which the monks were coming to devour with energy, if one might judge from their appearance. These sons of penitence and mortification possess one of the most spacious islands of the whole cluster, a princely habitation, with gardens and open porticos, that engross every breath of air; and, what adds not a little to the charms of their abode, is the facility of making excursions from it, whenever they have a mind.

The republic, jealous of ecclesiastical influence, connives at these amusing rambles, and, by encouraging the liberty of monks and churchmen, prevents their appearing too sacred and important in the eyes of the people, who have frequent proofs of their being mere flesh and blood, and that of the frailest composition. Had the rest of Italy been of the same opinion, and profited as much by Fra Paolo's maxims, some of its fairest fields would not, at this moment, lie uncultivated, and its ancient spirit might have revived. However, I can scarcely think the moment far distant, when it will assert its natural prerogatives, and look back upon the tiara, with all its host of idle fears and scaring phantoms, as the offspring of a distempered dream. Scarce a sovereign supports any longer this vain illusion, except the old woman of Hungary; and as soon as her dim eyes are closed, we shall probably witness great events*. Full of prophecies and bodings, I moved slowly out of the cloisters; and, gaining my gondola, arrived, I know not how, at the flights of steps which lead to the Redentore, a structure so simple and elegant, that I thought myself entering an antique temple, and looked about for the statue of the God of Delphi, or some other graceful divinity. A huge crucifix of bronze soon brought me to times present. The charm being thus dissolved, I began to perceive the shapes of rueful martyrs peeping out of the niches around, and the bushy beards of Capuchin friars wagging before the altars. These good fathers had decorated their church according to custom, with orange and citron trees, placed between the pilasters of the arcades; and on grand festivals, it seems, they turn the whole church into a bower, strew the pavement with leaves, and festoon the dome with flowers. I left them occupied with their plants and their devotions. It was mid-day, and I begged to be rowed to some woody island, where I might dine in shade and tranquillity. My gondoliers shot off in an instant; but, though they went at a very rapid rate, I wished to fly faster, and getting into a bark with six oars, swept along the waters, soon left the Zecca and San Marco behind; and, launching into the plains of shining sea, saw turret after turret, and isle after isle, fleeting before me. A pale greenish light ran along the shores of the distant continent, whose mountains seemed to catch the motion of my boat, and to fly with equal celerity. I had not much time to contemplate the beautiful effects on the waters -- the emerald and purple hues which gleamed along their surface. Our prow struck, foaming, against the walls of the Carthusian garden, before I recollected where I was, or could look attentively around me. Permission being obtained, I entered this cool retirement, and putting aside with my hands the boughs of figs and pomegranates, got under an ancient baytree on the summit of a little knoll, near which several tall pines lift themselves up to the breezes. I listened to the conversation they held, with a wind just flown from Greece, and charged, as well as I could understand this airy language, with many affectionate remembrances from their relations on Mount Ida. I reposed amidst bay-leaves, fanned by a constant air, till it pleased the fathers to send me some provisions, with a basket of fruit and wine. Two of them would wait upon me, and ask ten thousand questions about Lord George Gordon, and the American war. I, who was deeply engaged with the winds, and fancied myself hearing these rapid travellers relate their adventures, wished my interrogators in purgatory, and pleaded ignorance of the Italian language. This circumstance extricated me from my difficulties, and procured me a long interval of repose.