LETTER XX

Sienna, Oct. 26th.

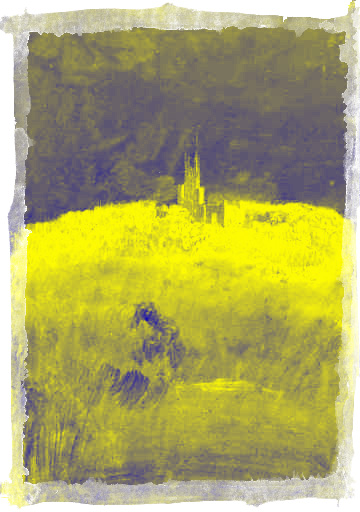

AT last, fears were overcome, the epidemical fever at Rome allowed to be no longer dangerous, and myself permitted to quit Florence. The weather was neither gay nor dismal; the country neither fine nor ugly; and your friend full as indifferent as the scenes he looked at. Towards afternoon, a thunder-storm gave character to the landscape, and we entered a narrow vale inclosed by rocks, with streams running at their base. Poplars with faded yellow leaves sprung from the margin of the rivulets, which seemed to lose themselves in the ruins of a castle, built in the gothic times. Our road led through its court, and passed the antient keep, still darkened by its turrets: a few mud cottages are scattered about the opening, where formerly the chieftain exercised his vassals, and trained them to war. The dungeon, once filled with miserable victims, serves only at present to confine a few goats, which were milking before its entrance. As we were driven along under a tottering gateway, and then through a plain, and up a hill, the breeze whispering amongst the fern which covers it, I felt the sober autumnal cast of the evening bring back the happy hours I passed last year, at this very time, calm and sequestered. Full of these recollections, my eyes closed of their own accord, and were not opened for many hours; in short, till we entered Sienna.

October 27th. Here my duty of course was to see the cathedral, and I got up much earlier than I wished, in order to perform it. I wonder that our holy ancestors did not choose a mountain at once, scrape it into tabernacles, and chisel it into scripture stories. It would have cost them almost as little trouble as the building in question, which may certainly be esteemed a masterpiece of ridiculous taste and elaborate absurdity. The front, encrusted with alabaster, is worked into a million of fretted arches and puzzling ornaments. There are statues without number, and relievos without end or meaning. The church within is all of black and white marble alternately; the roof blue and gold, with a profusion of silken banners hanging from it; and a cornice running above the principal arcade, composed entirely of bustos representing the whole series of sovereign pontiffs, from the first bishop of Rome to Adrian the Fourth. Pope Joan figured amongst them, between Leo the Fourth and Benedict the Third, till the year 1600, when she was turned out, at the instance of Clement the Eighth, to make room for Zacharias the First. I hardly knew which was the nave, or which the cross aisle, of this singular edifice, so perfect is the confusion of its parts. The pavement demands attention, being inlaid so curiously as to represent variety of histories taken from holy writ, and designed somewhat in the style of that hobgoblin tapestry which used to bestare the walls of our ancestors. Near the high altar stands the strangest of pulpits, supported by polished pillars of granite, rising from lions' backs, which serve as pedestals. In every corner of the place some chapel or other offends or astonishes you. That, however, of the Chigi family, it must be allowed, has infinite merit with respect to design and execution; but it is so lost in general disorder as to want the best part of its effect.

From the church one enters a vaulted chamber, erected by the Picoliminis, filled with valuable missals most exquisitely illuminated. The paintings in fresco on the walls are rather barbarous, though executed after the designs of the mighty Raffaelle; but then we must remember, he had but just escaped from Pietro Perugino. Not staying long in the Duomo, we left Sienna in good time; and, after being shaken and tumbled in the worst roads that ever pretended to be made use of, found ourselves beneath the rough mountains round Radicofani, about seven o'clock on a cold and dismal evening. Up we toiled a steep craggy ascent, and reached at length the inn upon its summit. My heart sunk when I entered a vast range of apartments, with high black roofs, once intended for a hunting palace of the Grand Dukes, but now desolate and forlorn. The wind having risen, every door began to shake, and every board substituted for a window to clatter, as if the severe power who dwells on the topmost peak of Radicofani, according to its village mythologists, was about to visit his abode. My only spell to keep him at a distance was kindling an enormous fire, whose charitable gleams cheered my spirits, and gave them a quicker flow. Yet, for some minutes, I never ceased looking, now to the right, now to the left, up at the dark beams, and down the long passages, where the pavement, broken up in several places, and earth newly strewn about, seemed to indicate that something horrid was concealed below. A grim fraternity of cats kept whisking backwards and forwards in these dreary avenues, which I am apt to imagine is the very identical scene of a sabbath of witches at certain periods. Not venturing to explore them, I fastened my door, pitched my bed opposite the hearth, which glowed with embers, and crept under the coverlids, hardly venturing to go to sleep lest I should be suddenly roused from it by the sudden glare of torches, and be more initiated than I wished into the mysteries of the place. Scarce was I settled, before two or three of the brotherhood just mentioned stalked in at a little opening under the door. I insisted upon their moving off faster than they had entered, suspecting they would soon turn wizards, and was surprised, when midnight came, to hear nothing more than their mewings, doleful enough, and echoed by the hollow walls and arches.

Additional letters, I-VII

An Excursion to the Grande Chartreuse in the year 1778