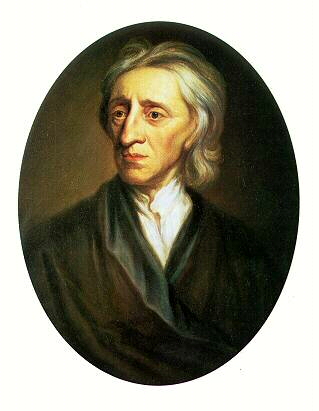

John Locke (1632-1704), author of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, a cornerstone of Beckford's early education.

»A Letter from Geneva, May 22, 1778»

[Ms Beckford d.9, fols. 34-43]

[1] Dear Sir,

As you did me the honour to say a Letter from me would not be disagreeable I should have taken an earlier opportunity of writing had I not conceived some merit in not intruding too forwardly on your important engagements.

I have now passed almost a Year at Geneva and I don’t know what I can better make the Subject of my Letter than some account of what I have been doing here and of some of the principal Characters, whose Acquaintance I have chiefly cultivated with a view to the improvement of my Time. Having for some time been persuaded that our Countryman Mr Lock has discovered the same sources of our knowledge, however short my application may have fallen of the wishes of my Friends, I cannot accuse myself of having sat still to wait for the devellopment of Innate Ideas and having no pretensions to [2] Inspiration I have believed myself fairly left to the use of my Five Senses and a little reflection for the first materials of my knowledge. Simply to stock my Mind with Ideas and with Words to express them I suppose to have been the proper business of my earliest Years, and partly that of Education to direct me to those most worth acquiring. I dare not but flatter myself some little stores may have been thus gained to Memory. The natural Enquiry is what use I have made of them. I learn from the great Master of human Knowledge /just mentioned/ that there are two other powers which claim a right to the free use of these primary acquisitions. One delights to disjoin, or jumble them together with the wildest Caprice, and cares not for method, arrangement, or any thing else provided she holds up a pleasant Picture to the Mind. The other a grave and respectable Matron resolutely calls to Order, claims the Rule of the Ideal World and thinks it enough, that the former should stand second in the intellectual Sovereignty. Her object is to change the whole Face of things; [3] she will not suffer the treasures, which memory has been collecting, to rest in their first State, unmeaning and passive, nor on the other hand to be heaped and huddled together at the arbitrary suggestions of Fancy. It is her province to marshal them in Order to examine their relation or disagreement, and to chain down each to its proper place. If now I return to the Enquiry into my own Conduct under the Influence of these two contending powers, I fear I shall stand self-convicted of having sacrificed a little to freely to Imagination. –

Numberless Ideas have I put asunder which Judgement would have joined; as many have I closely linked, where she has forbidden the Alliance. I may however boast the Merit of being at length brought to some sense of Duty in this affair, and of having at last resolved to subject my Imagination to the Dominions of her Rival. Whether the Steps I have taken are likely to effect my purpose is submitted to your opinion; I am going to trouble you [4] with them. – Having chiefly attached myself, whilst in England to Classical, Historical and moral Studies with some of their auxiliary Branches of Knowledge, I have, since my residence here enlarged the plan of my pursuits and have entered about six Months ago, on a Course of Experimental Lectures in Physics with Mr D’Espinas who formerly gave Lessons to several of the Royal Family and has brought from England a very noble Apparatus. As he is allowed to conduct his experiments with the severest reasoning, I hope I am, at the same time, making some advances in Logic and perhaps learning it in the best way. - -

The English Philosophy has gained great Credit by our late discoveries in Electricity and fixed Air. The names of Franklin and Priestly are in high estimation at Geneva. The Civil Law still keeping its authority in this Republic is a good deal cultivated, and Geneva continues to produce Civilians of [5] distinguished abilities. – This advantageous circumstance joined with the Consideration of Justinian’s giving the Law in some of our own Tribunals and influencing in some measure the legislation of most of the Countries in Europe, has tempted me to undertake a review of this System of written reason in a Course of Lessons with an Advocate of reputation. As far as our time has admitted Mr Lettice and I have accompanied this Course with the reading of Montesquieu and Blackstone. If I had an opportunity, I believe I should attempt a parallel betwixt the Roman Law and that of England. An exercise of this kind might not only contribute to fix both in my Memory; but impress more deeply the Characteristic differences of each, which, for the happiness of our Country, are very considerable. We make some use of the Elements of Hennecius, esteemed here the best of the Commentators. His general method is, to give first the Definition of each Subject, and then to collect the Spirit of all the Laws upon it into two or three [6] concise anxioms. The several Cases and Circumstances, to which they apply, are next deduced as necessary at least as natural consequences and he concludes with shewing how far each Law obtains at present in those Countries, where Justinian still maintain his Credit. I find this method clear and interesting; it at once makes the spirit of the Law intelligible and not very difficult to retain. These objects added to my former Studies, with some application to the Spanish, Italian & Oriental Languages and an attention to my Exercises have found me sufficient employment, and such as I hope my best Friends and particularly yourself will not disapprove. - - -

Having said full enough and I fear too much of myself, I will give you a slight sketch of some of those persons whose conversation I have chiefly sought here; some of whose Names you are probably not unacquainted with. - - -

I luckily caught the moment of seeing Voltaire before his [7] setting on our Horizon. –

All we shall ever see of him more at Geneva is the light of his Genius reflected from his Works.

I will next present to you a less brilliant but far more sedate & moral personage Bonnet de G[?] from whom I have received a thousand flattering marks of kindness and affection. This Gentleman, since Linneus and Mallet are gone, may perhaps justly claim the first Rank in the walk of Natural History. It may be doubted whether his Vocabulary in this Language be of equal extent with theirs; but his experiments and discoveries shew him to have interrogated Nature with at least as much, if not more Sagacity than either of them. He is not less eminently distinguished in Metaphysics: He has endeavoured to strengthen the foundations of this Science by the application of some important discoveries in Natural History. [8] His System of the Germ or Corps indistructible is placed on the Ruins of Buffon’s organic molecules. He appears on many occasions a warm Advocate for Leibnitz’s pre-established Harmony; tho’ he by no means adopts it in its full extent.

Mr Bonnet possesses in common with Fenelon and Gravesend the rare talent of composing whole Works without writing a Letter and that so correctly, as scarcely to change a Word when he commits them to paper. He was bred to the Law and is said to have shone in his profession; but his propensity to meditation and retirement occasioned his quitting the Bar at a very early period of Life. He lives upon his Fortune at an agreeable Villa on the Lake in the elegant Commerce of literary Men and is visited by most Strangers of Distinction and Merit who come to Geneva. - - - - -

Mr De Saussure possesses the Chair of Natural Philosophy and it is but just to infer, that he is a Philosopher. All the World [9] however agrees, that Mr De Saussure has a comely Person, a fine House, a spruce Apparatus and a Cabinet of Natural History so amiably arranged that Philosophy with him seems to have thrown aside her Beard and Savage Air and to be attired by the Smiles and the Graces. –

Mr Frouchin de la Boissiere, called here the Montesquieu of the Age is in Person, a striking contrast to Mr De Saussure.

He is unquestionably a Man of Genius and uncommon acquisitions in various parts of Literature. His attention has chiefly been turned to Law, Politics and History. He has perhaps a more general intelligence in the politics of Europe than any Man not particularly concerned in them. His Lettres de la Campagne gave occasion to the very celebrated ones de la Montagne of Rousseau.

The opposite principles violently insisted on in the one and the other have kept this Republic in perpetual agitation since the Year 1765. Rousseau having long renounced all personal interference in the Genevan Contest, Mr Frouchin remains the sole Oracle. - -

[10] He lives wrapped up in the Groves of his Villa, apparently retired from all political Concerns and if consulted at present, it is not without the affectations of a very mysterious secrecy.

Mr Mallet, Professor of History, was formerly employed in the education of the King of Denmark. The Tutor approaches much nearer to Aristotle than the Pupil to Alexander. - - - -

Whilst in this situation Mr Mallet found opportunity to cultivate the antiquities of the North. He has particularly explored the Customs, Manners and Mythology of the antient Scandinavians, which he has displayed at large in the very interesting and elegant Introduction to his History of Denmark. His acquaintance with polite Literature in general is reckoned very extensive. His manners and conversation are correct and easy without any of those insipid prettinesses, the common gingerbread guilding of Courtly Characters. He enjoys the first Consideration here and I have had the happiness of living a good deal with him. - - - - - -

[11] Mr Senebier, the learned Librarian of Geneva, pursues many different branches of Literature with indefatigable application and most of them with success. In physics he has shewn himself a watchful Observer of Nature and at a very early Age published his L’Art d’observer; a Work of merit. He has acquired more than a common knowledge of the Learned Languages both ancient and modern and has justified his pretensions to Criticism by several well written Articles in Literary Journals of France and by other Essays of Taste. - -

In the province of Antiquary and Biographer he has almost finished the Literary History of Geneva; a curious and interesting Work which he means to give to the World at his leisure and with a Sight of which I have been already favoured. - - -

He has now in the Press a very ingenious Treatise, the Object of which is to ascertain the age of antient Manuscripts. –

The public in the Course of last Winter has been indebted to Mr Senebier’s pen for a very spirited Eulogy of the late Baron [12] Haller and the first Volume of the Memoirs of the Academy of Arts at Geneva. The Literature of France has likewise received some valuable accessions in several foreign Works of eminence translated by him and particularly the Reproductions Animales of the famous Italian Naturalist Spallanzani. As this Gentleman writes where other Men speak, and in short does nothing without Book he paid his addresses to his Wife in a sentimentel Novel; but as Nature formed him rather to think than to feel, it is questioned, whether all the Fame he has gained by this gallant piece of Work extends beyond the narrow sphere of the Lady’s opinion. - - -

Mr Bertrand presides in the mathematical Chair with great ability and reputation. He is distinguished by the Liberality of his Sentiments and a very masculine Understanding. He is about to publish a Work in the Science he professes, in which some useful discoveries are expected from him. He possesses a good deal of information on various Subjects, which he displays very agreeably in the Conversation of his friends.

[13] There is something singularly attractive in his Manners. As he sometimes takes an active part in the affairs of the Republic his civil Character is marked by an intelligible upright and decisive Conduct. - - -

Mr le Syndic Turretini is too conspicuously placed not to command my respects upon this occasion. He is visible head of a Commission appointed to form a new Code of Laws for the Republic. He is favoured with the gift of Tongues in a superior degree and deluges a Conversation with Words in half a Dozen Languages. - -

When the present King of Sardinia visited the Frontiers of Savoy, Mr Turretini was chosen to present his Majesty the Devoirs of the State. (By the way, I believe the Conduct of this Ceremony with the Adjustment of some little differences about a few Acres of Territory has sometimes been stiled Mr Turrettini’s Embassy) On all similar occasions this Syndic is made the Organ of the fine speeches of the Republic. His managements betwixt the two parties of the Commonwealth have now and then exhibited something a little problematical to the [14] politicians of Geneva. - -

He is reckoned an able Civilian and is allowed to have acquitted himself with Eclat as Mr De Saussure’s Predecessor in the Professorship of Natural Philosophy.

Mr Moulton was formerly of the Church and admired as an accomplished Orator. I am not acquainted with the Motives which induced him to quit his profession. His Fortune must undoubtedly have rendered him indifferent to its emoluments; but he is not a Man to act upon negative Reason only. A great share of Genius and Learning united with Taste and Delicacy of Manners from the Ground of his Character, which is still rendered more affecting by a deep shade of melancholy. - -

The Charms of his Understanding have won him the esteem of Voltaire, the sensibility of his Heart has endeared him to Rousseau.

His enthusiasms for Freedom, which has probably had its share in engaging him the friendship of the latter, has secured [15] him the affection of the Citizens of Geneva, who assure themselves his influence will give a little of the genial warmth of Liberty to the Aristocratic phlegm of the Code. He is lately gone to Paris to read Rousseau’s Memoirs of his own life, and is supposed to be almost the only person to whom they are to be communicated before the Death of their Author. It is not improbable his Design is to submit in his turn an Idea of the Genevan Code to the inspection of his Friend. - - - - - -

Mr Vernet the theological professor, boasts a presence of Mind and Vigour of Constitution equally uncommon at Fourscore and four.

I know not whether our Nestor in the World of Letters may not be said to have seen two Generations pass away and to live in the third. He may make the same reflection on the literary Race, which the Sage of Pilos does on the natural.

Having been engaged in Controversy he often recounts his polemical scars. He is well versed in antient learning and profoundly Master of that of France. He has known and lived [16] with many of the great Men, who figured in the Annals of Louis XIV; as well as with the brightest of their Successors: It makes the chief Amusement of his old Age to relate their Memoirs and Anecdotes and to describe their Characters and Writings, As Homer’s Sage would recite the warlike Actions of a Theseus, or Polyphemus, our venerable Professor celebrates the Literary Achievements of a Huygens, or Cassini. We hear how the former taught the Pendulum to vibrate in the Cycloid, and the latter subjected to the Empire of Science the inundations of the Po. – Sometimes we follow him thro’ the paradoxes of a Hardouin and the peregrinations of Saint Peter shadowed forth in the Æneid, are led with rapture thro Fontenelles’ plurality of Worlds, or taught to choose the best with Massilon, or Saurin. I have frequently heard him harangue a Literary Circle on some point of Erudition for the Space of half an hour together, which he does with a Compass of knowledge and facility of expression that would not have dishonoured his most rigorous years. Thus at an Age which seldom offers anything to notice but what excites mortification, Mr Vernet is the delight of [not numbered [17]] of [sic] every Society he enters. - - - -

His learned and liberal researches in his own profession will probably secure him the regard of a future Generation, as a life that corresponds to the Doctrine he preaches, attracts the Veneration of this. - -

In Mr Huber I introduce to your acquaintance a Genius so wild, so irregular, so various, a Camelion that presents himself under so many different Colours almost at once, that I know not which to call most properly his own, nor which I shall attempt to catch first in the rapid succession. I see him this moment starting from his Chair with his Instrument in his hand and playing an Italian Air with all the fire, feeling and expressions of a great Master. Now he sits down and instructs his Friends with a solemn dissertation on the present state of Europe. He has just snatched up his Scissars and is cutting at figures in paper. What an unworthy amusement, some Stranger exclaims; It is Hercules with his Distaff! – But all is consecrated in his hands. We are [18] presently astonished with a fine Landscape a beautiful assemblage of picturesque Objects, or perhaps a Colossal Hero frowning in paste-board. The Scissars however are not Mr Huber’s only Instrument of Design. At the age of forty, he took up the Pencil. We have scarcely time to admire the wonders he works with it, before we find him passionately occupied in examining the Nature, Gravity and pressure of Fluids. Whilst his Friends are promising another Archimedes or Boyle to the Science of Hydrostatics, he is suddenly engaged in a Treatise on Falconry and his Imagination is soaring into the Clouds with his Hawks. At this Moment he comes reeking from his Diversion all over blood and filth with Lures and Coping Irons, dangling about him. We meet him next in the Drawing Room transformed into a fine Gentleman and entertaining the Italian, the Spaniard, the German or the Englishman, each in his own Language, with descriptions, anecdotes or customs, of their several Countries.

His discernment instantly seizes the ridicule of every Character, [19] which, at certain intervals, he seldom fails to reflect back in the most vivid colouring that Mimickry and Wit can furnish. After so many strange Instances of Versatility we are not surprized to see him dispensing Justice in one of the Tribunals of the Commonwealth, nor, as soon as he is escaped to his Villa from the Tramels of Business, exulting in the Views of the Lake, the Woods and Mountains around him and describing their effects in the Language of Inspiration.

When I cast my eye back on some of the Traits of the original I have been drawing, I know not whether I should apologize for the fidelity of my piece: Unless however you should condescend to correct me, I shall be half inclined to think they ought not to have been omitted. –

Here Sir, I have presented to you a respectable Company, to whom I am indebted for the pleasures of the most agreeable Society. I could much have enlarged the number by the distinguished Names of Le Sage, Tremblay, De Rochmont, a Claperede and a De Lolme; but that I have wanted opportunities of [20] cultivating them sufficiently to do justice to their merit. I may add too that I have all along felt some discouragement under the idea of addressing these pourtraits to a Gentleman whose own Character presents one so superior to them all.

I have the honour to be

Dear Sir

Your Obedient and Obliged

Humble Servant

William Beckford

Thanex[?]

May 22d

1778

Introduction to »A Letter from Geneva, May 22, 1778»As William Beckford, just prior to his seventeenth birthday, arrived in Geneva in the summer of 1777 together with his tutor, John Lettice, he entered into an ambitious regime of education softened by the presence of much admired intellectual giants and sweetened by the freedom offered by life on the continent. Though studying many topics which would be beneficial to the young heir in his future life, Beckford also devoted much time to other, more artistic pursuits. His biographers have made much of his separation from his friend and drawing-master Alexander Cozens during this period and have drawn upon letters written to him, from Geneva, in which Beckford outlines a parallell life, smoothly and safely out of sight of his appointed guardians. This life was led by Beckford in a world of imagination. The writer, the artist, the intellectual and the aesthete – all these roles were assumed by Beckford as he read, dreamt and conversed freely with the intelligentsia of Geneva.

Beckford stayed in Switzerland for almost a year and a half. In May of 1778, he found time to write a lengthy report to his guardian, Lord Thurlow, about his education and his experiences in Geneva. The letter, which survives in a fair copy dated May 22, 1778, is a chatty yet informative account of his acquaintances and his studies. It offers a cross-section of the intellectual clique in Geneva at the time, and provides the reader with a rare glimpse into the continental education of a wealthy heir. It is also an implicit reminder of Beckford’s real interests at the time. Apologetic, the letter begins with an interesting excursion into the double life of the aspiring artist, torn between the conflicting powers of reason and fancy.

The fair copy of the letter is contained within the covers of a small book which, somewhat surprisingly, also contains a draft of Beckford’s short prose work »Hylas». The letter is written in the hand of an amanuensis, as are many of Beckford’s letters in fair copy, and spans twenty small pages. The present edition, which is transcribed with as much accuracy as is possible, retains the various spelling idiosyncrasies which are an inevitable aspect of all of Beckford’s manuscripts. No explanatory footnotes are provided, and it is the expressed hope of the editor that the publication of the letter will spawn a discussion of the intellectual climate into which Beckford descended in the summer of 1777, a discussion which will no doubt shed new light on Beckford’s intellectual and artistic development.

All words underlined in the manuscript have been rendered in italics. The original pagination has been retained within square brackets. The manuscript, which is found on fols. 34-43 in MS Beckford d.9, is published with the kind permission of the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Dick Claésson[This edition was originally published in the Beckford Journal, Spring 2001, pp. 18-29]