PORTRAITS AND BIOGRAPHY

OF

PUBLIC CHARACTERS

Saturday, No. 18. Oct., 4, 1823.

THE

UNIQUE:

A

Series of Portraits

OF

EMINENT PERSONS.

WITH THEIR MEMOIRS.

”Prize little things, nor think it ill

That men small things preserve.” – Cowley

LONDON:

Printed and Sold by GEO. SMEETON, 15, Royal Arcade,

Pall Mall; LIMBIRD, (Mirror Office,) 355, Strand, and

all Booksellers and Newsmen.

PRICE TWO-PENCE.

WILLIAM BECKFORD, ESQ.

This celebrated gentleman is of royal and noble descent: as appears by an

order registered in the Herald’s College, bearing date 20th March, 1810,

which recites that his father (the celebrated Lord Mayor of London, whose

statue is in the Guildhall, London,) married Maria, daughter and at length

co-heir of the honourable George Hamilton, who was the second surviving son

of James, the sixth Earl of Abercorn. This lady was descended, in a direct

line, from James, the second Lord Hamilton, by the Princess Mary Stuart, his

wife, eldest daughter of James II. King of Scotland.

Mr. Beckford married the Lady Margaret Gordon, only daughter of Charles, late

Earl of Aboyne, by whom he has issue two daughters, namely, Margaret Maria

Elizabeth Beckford, and Susanna Euphemia Beckford, who married the present

Duke of Hamilton.

It is remarkable that individuals of three branches of the noble house of

Howard are descended from the family of Beckford; viz. 1. Henry Howard, Esq.

(only son of Lord Henry Molyneux-Howard and nephew to the present Duke of

Norfolk), whose grandmother, Mary Ballard Long, was daughter and heir to Thomas

Beckford, Esq. grandson of Peter Beckford, Esq. Lieutenant-Governor of Jamaica.

2. Charles Augustus Ellis, Lord Howard de Walden (of the Suffolk branch of

Howard), whose great-grandmother Anne, the wife of George Ellis, Esq. was

elder sister to the Countess of Effingham, and aunt to the present Mr. Beckford.

3. Thomas and Richard, the two last Earls of Effingham, sons of the above

Countess.

Mr. Beckford, on coming possessed of his fortune, made the grand tour, and

resided many years in Italy; it was here that he improved that exquisite taste

and love of [ii] the Fine Arts, for which he is pre-eminent. On his return

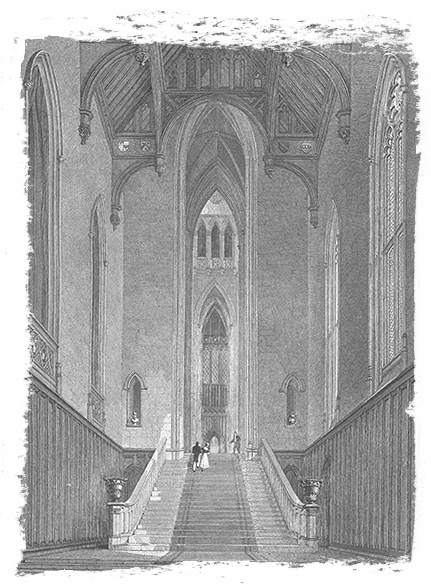

to England, he resolved on building Fonthill – which he accomplished;

and in August, 1822, he as hastily determined to dispose of it – and

accordingly gave directions to that eminent auctioneer, Mr. Christie, of Pall-Mall,

London, to dispose of it; and so great was the anxiety to view the splendid

edifice, that upwards of 9000 catalogues, at one guinea each, were sold before

the day of the sale; on the day preceding which, to the surprise and mortification

of the public, notice was given that the estate of Fonthill, with all its

immense treasures, was sold to Mr. Farquhar for 300,000l. This gentleman has

since employed Mr. Phillips to sell the whole of the effects, which will occupy

thirty-nine days!

We are told the possessor of this splendid treasure left it almost without

a pang. His first resolution was to build a cottage lower down in the demesne,

near the fine pond, and let the Abbey go to ruin. ”I can live here,”

he said to his woodman, ”in peace and retirement for four thousand a

year – why should I tenant that structure with a retinue that costs

me near thirty thousand?” Subsequently, however, he resolved to part

with the entire, and announced his intention without a sigh. ”It has

cost me,” said he (gazing at it), ”with what it contains, near

a million. Yet I must leave it, and I can do so at once. Public surprise will

be created, but that I am prepared for. Beckford, they will say, has squandered

his large fortune: to me it is a matter of perfect indifference.”

It would much exceed our limits to attempt even a description of this justly

celebrated Fonthill.

On one occasion, whilst the tower was rearing its lofty crest towards Heaven,

an elevated part of it caught fire, and was destroyed. The sight was sublime;

it was a spectacle, it is said, which the owner of the mansion enjoyed with

as much composure as if the flames had not been devouring what it would have

cost a fortune to repair. This occasioned but a small delay in its re-creation,

as the building was carried on by [iii] Mr. Beckford with an energy and enthusiasm,

of which duller minds can form but a poor conception. At one period, it is

said, that every cart and waggon in the district were pressed into the service,

though all the agricultural labours of the country stood still. At another,

even the royal works of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, were abandoned,

that 460 men might be employed, night and day, on Fonthill Abbey. These men

relieved each other by regular watches, and during the longest and darkest

nights of winter, the astonished traveller might see the tower rising under

their hands, the trowel and torch being associated for that purpose. This

must have had a very extraordinary appearance, and it is said, was another

of those exhibitions which Mr. Beckford was fond of contemplating. –

He is represented as surveying the work thus expedited, the busy levy of the

masons, the high and giddy dancing of the lights, and the strange effects

produced on the woods and architecture below, from one of those eminences

in the walks, of which there are several; and wasting the coldest hours of

December’s darkness, in feasting his sense with this display of almost

super-human power. He had, for a long time, more than four hundred persons

employed at both, who were regularly paid every week. The works went constantly

on; there have been instances of individuals paid for sixteen days’

work during a week, including Sunday as a double day. Mr. Beckford superintended

all himself. He stood amid torch-light, urging on the growth of the Abbey

towers, and rode during the day among his labourers to see the plantations

made. These traits of character will not surprise those who have made mankind

their study: the minds most nearly allied to genius, are the most apt to plunge

into extremes, and no man at present in existence, can make higher pretensions

to a mind of this cast, than the founder of Fonthill Abbey.

Mr. Beckford’s style of living, as described by persons who had daily

opportunities of witnessing it, is calculated to excite surprise and astonishment.

The gorgeous [iv] array of the banquet he provided for Lord Nelson and Lady

Hamilton has long since been detailed with all its splendid attributes of

pomp; but his ordinary mode of living, which regarded only himself and his

solitary foreign guest, was costly and luxurious beyond what the most extravagant

Englishman could possibly imagine. He allowed his cook 800l. a year, and appropriated

2000l. a month to supply provisions for his kitchen. He has been known on

frequent occasions to sit down with Franchi, (for there was scarcely ever

a third person at table) to a dinner consisting of twenty covers, served upon

gold plate. Meanwhile the servants were all stationed in a line of communication

between the dining room, the pantry, and the kitchen, so that they were in

constant readiness to pass his orders from one to another. With him the words

servant and slave were synonymous, and he considered it derogatory to his

dignity not to have a train of menials waiting his commands at all hours.

He was as despotic in this respect as an Eastern Rajah, yet at the same time

never was any man more liberal to his servants. They not only enjoyed his

bounty, but shared his magnificence, and while they trembled at his nod, they

feasted on viands with which the first potentates of the earth might regale

themselves.

Among the many anecdotes of this gentleman, the following is related: –

Mr. Beckford resolved on going to Italy, and accordingly purchased two vessels

and fitted them up in the greatest magnificence: he had scarcely been at sea

a day, before he encountered a stiffish breeze, which continued one night

and part of the next day, during which time the vessels made but little way

on their voyage: this so enraged Mr. B. that he summoned the captain to his

presence, and asked him how long he imagined the breeze would continue. ”Perhaps,

Sir,” says the captain, ”it may last another day or so.”

”Another day!” replied Mr. B. ”land me, my servants, and

the carriages immediately at the first port.” This order was obeyed;

and Mr. B. remained on shore, [v] making the captain a present of the vessels

for his trouble.

It is not, perhaps, generally known that no man living is more fanatically

superstitious than Mr. Beckford. He is said, while he resided here, to have

had so great a veneration for St. Anthony, that when he once made a vow in

his name he never in any instance failed to fulfil it. A ludicrous proof of

this occurred while he was building the Abbey. He vowed, by all the power

of his favourite Saint, that he must have his Kitchen built within a certain

number of days, so that his Christmas dinner should be cooked in it. The workmen

knew right well that the vow was not made in vain. The plied their labours

incessantly; the kitchen was actually built; but in consequence of the extreme

wetness of the weather the mortar could not cement the stone and brick-work.

The Christmas dinner was, however, cooked in time to save Mr. Beckford’s

conscience, but scarcely was it dished for dinner when the walls of the kitchen

tumbled about the ears of the domestics. Fortunately nobody was injured by

the crash, for it gave just notice enough for them to escape its effects.

How strange that a man of Mr. Beckford’s great intellectual powers and

vast attainment should labour under such an influence!

Mr. Beckford, it is generally supposed, possesses little now beyond the remnants

of what he acquired by the sale of Fonthill. His once magnificent income has

fallen to almost nothing. He lost a large portion of his West India estates

from defect of title, after a most expensive legal contest of several years,

and was subjected to the heavy arrears of produce while he held them. So far

from deriving any thing from the remnant of those once proud possessions,

there was last year a loss on the expenditure and produce of 200l. Mr. Beckford

possessed a fine taste, but he attached little value to any thing that was

not costly, and is said to have been long the dupe of picture-dealers and

collectors. His establishment, too, for years, was most lavishly expensive.

”The lazy vermin of the hall, those trappings of his folly,” swarmed

[vi] at Fonthill. Mr. Beckford never moved but with a circle of them in attendance.

They formed an appendage of his invincible pride; there was not a bell throughout

the entire Abbey; but he needed no summons to command attendance. His liveried

retainers stood, in numerous successions, watchful sentinels at his door,

and at fixed periods anticipated their proud master’s wants. With all

this expense few visitors were ever seen within the Abbey gates, and his own

habits were most temperate. The Chevalier Franchi had been his companion for

years; Mr. Beckford met him, we believe, in Portugal. The Chevalier was then

a married man, and with a family, but was induced to attend his patron to

England: his wife and children did not, however, accompany him, or quit Portugal

during the many years the Chevalier remained in England. He acted for several

years as comptroller of the household at Fonthill, is said to be a man of

very cultivated mind, and is now with Mr. Beckford at Bath, who took from

the Abbey 16 or 18 servants with him beside. Soon after the latter’s

first visit to Portugal, he became, it is generally supposed, a Catholic,

and a member of the monastic order of St. Anthony. The Chevalier Franchi was

also an extern associate of that order, and initiated with Mr. Beckford in

its mysteries: both always wore the cross of the order, as a distinguishing

character, in their breasts; and, like Louis XI. of France, Mr. Beckford always

carried about him a small silver image of the saint. He had also in his chamber

a picture of the Anchoret, to which he addressed his constant orisons. Mr.

Beckford for years rose early, and retired as early to rest. He read constantly

during the evening; half the books in the library bear marks of his studies;

his days, with few exceptions, were devoted to the improvements in the building

and demesne.