William Hazlitt

Sketches of the Picture Galleries of England (1824)

[text from Criticisms on Art: and Sketches of the Picture Galleries of England,

London 1856, second edition, pp. 284-299

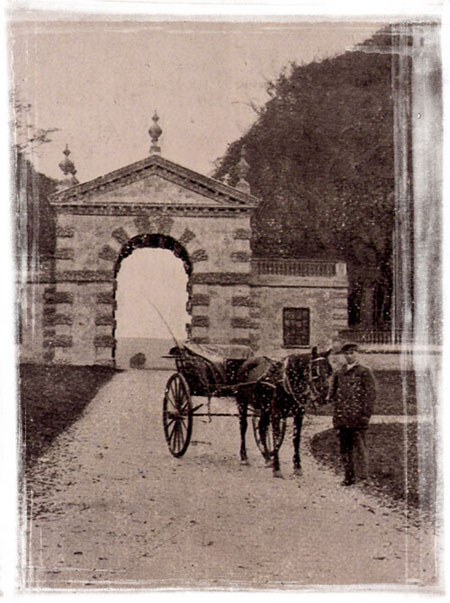

FONTHILL

ABBEY.

The old sarcasm – Omne ignotum pro magnifico est – cannot be justly

applied here. FONTHILL ABBEY, after being enveloped in impenetrable mystery

for a length of years, has been unexpectedly thrown open to the vulgar gaze,

and has lost none of its reputation for magnificence – though, perhaps,

its visionary glory, its classic renown, have vanished from the public mind

for ever. It is, in a word, a desert of magnificence, a glittering waste of

laborious idleness, a cathedral turned into a toy-shop, an immense Museum of

all that is most curious and costly, and, at the same time, most worthless,

in the productions of art and nature. Ships of pearl and seas of amber are

scarce a fable here – a nautilus's shell surmounted with a gilt triumph

of Neptune – tables of agate, cabinets of ebony, and precious stones,

painted windows "shedding a gaudy, crimson light," satin borders,

marble floors, and lamps of solid gold – Chinese pagodas and Per- [285]

sian tapestry - all the splendour of Solomon's Temple is displayed to the view – in

miniature whatever is far-fetched and dear-bought, rich in the materials, or

rare and difficult in the workmanship – but scarce one genuine work of

art, one solid proof of taste, one lofty relic of sentiment or imagination!

The difficult, the unattainable, the exclusive, are to be found here in profusion,

in perfection, all else is wanting, or is brought in merely as a foil or as

a stop-gap. In this respect the collection is as satisfactory as it is unique.

The spemens exhibited are the best, the most highly finished, the most costly

and curious, of that kind of ostentatious magnificence which is calculated

to gratify the sense of property in the owner, and to excite the wondering

curiosity of the stranger, who is permitted to see or (as a choice privilege

and favour) even to touch baubles so dazzling and of such exquisite nicety

of execution; and which, if broken or defaced, it would be next to impossible

to replace. The same character extends to the pictures, vhich are mere furniture-pictures

remarkable chiefly for their antiquity or painful finishing, without beauty,

without interest, and with about the same pretensions to attract the eye or

delight the fancy as a well-polished mahogany table or a waxed oak-floor. Not

one great work by one great name, scarce one or two of the worst specimens

of the first masters; Lionardo's Laughing Boy, or a copy [286] from Raphael,

or Correggio, as if to make the thing remote and finical - but heaps of the

most elaborate pieces of the worst of the Dutch masters, Breughel's Sea-horns

with coats of mother-of-pearl, and Rothenhamer's Elements turned into a Flower-piece.

The Catalogue, in short, is guiltless of the names of any of those works of

art

Which like a trumpet make the spirits dance;

and is sacred to those which rank no higher than veneering, and where the painter

is on a precise par with the carver and gilder. Such is not our taste in art;

and we confess we should have been a little disappointed in viewing Fonthill,

had not our expectations been disabused beforehand. Oh! for a glimpse of the

Escurial! where the piles of Titians lie; where nymphs, fairer than lilies,

repose in green, airy, pastoral landscapes, and Cupids, with curled locks,

pluck the wanton vine; at whose beauty, whose splendour, whose truth and freshness,

Mengs could not contain his astonishment, nor Cumberland his raptures;

While groves of Eden, vanish'd now so long,

Live in description, and look green in song;

the very thought of which, in that monastic seclusion and low dell, surrounded

by craggy precipices, gives the mind a calenture, a longing desire to plunge

through wastes and wilds, to [287] visit at the shrine of such beauty, and

be buried in the bosom of such verdant sweetness. – Get thee behind us,

Temptation; or not all China and Japan will detain us, and this article will

be left unfinished, or found (as a volume of Keats's poems was carried out

by Mr. Ritchie to be dropped in the Great Desert) in the sorriest inn in the

farthest part of Spain, or in the marble baths of the Moorish Alhambra, or

amidst the ruins of Tadmor, or in barbaric palaces, where Bruce encountered

Abyssinian queens! Any thing to get all this frippery, and finery, and tinsel,

and glitter, and embossing, and system of tantalization, and fret-work of the

imagination out of our heads, and take one deep, long, oblivious draught of

the romantic and marvellous, the thirst of which the fame of Fonthill Abbey

has raised in us, but not satisfied!

Mr. Beckford has undoubtedly shown himself an industrious bijoutier, a prodigious

virtuoso, an accomplished patron of unproductive labour, an enthusiastic collector

of expensive trifles – the only proof of taste (to our thinking) he has

shown in this collection is his getting rid of it. What splendour, what grace,

what grandeur might he substitute in lieu of it! What a handwriting might be

spread out upon the walls! What a spirit of poetry and philosophy might breathe

there! What a solemn gloom, what gay vistas of fancy, like chequered light

and shade, might genius, guided by art, shed around! The [288] author of Vathek

is a scholar; the proprietor of Fonthill has travelled abroad, and has seen

all the finest remains of antiquity and boasted specimens of modern art. Why

not lay his hands on some of these? He had power to carry them away. One might

have expected to see, at least, a few fine old pictures, marble copies of the

celebrated statues, the Apollo, the Venus, the Dying Gladiator, the Antinous,

antique vases with their elegant sculptures, or casts from them, coins, medals,

bas-reliefs, something connected with the beautiful forms of external nature,

or with what is great in the mind or memorable in the history of man, – Egyptian

hieroglyphics, or Chaldee manuscripts on paper made of the reeds of the Nile,

or mummies from the Pyramids! Not so; not a trace (or scarcely so) of any of

these; – as little as may be of what is classical or imposing to the

imagination from association or well-founded prejudice; hardly an article of

any consequence that does not seem to be labelled to the following effect -

This is mine, and there is no one else in the whole world in whom it can inspire

the least interest, or any feeling beyond a momentary surprise! To show another

your property is an act in itself ungracious, or null and void. It excites

no pleasure from sympathy. Every one must have remarked the difference in his

feelings on entering a venerable old cathedral, for instance, and a modern

built private mansion. The one seems to fill [289] the mind and expand the

form, while the other only produces a sense of listless vacuity, and disposes

us to shrink into our own littleness.

Whence is this, but that in the first case our associations of power, of interest,

are general, and tend to aggrandize the species; and that, in the latter (viz.

the case of private property) they are exclusive and tend to aggrandize none

but the individual? This must be the effect, unless there is something grand

or beautiful in the objects themselves that makes us forget the distinction

of mere property, as from the noble architecture or great antiquity of a building;

or unless they remind us of common and universal nature, as pictures, statues

do, like so many mirrors, reflecting the external landscape, and carrying us

out of the magic circle of self-love. But all works of art come under the head

of property or showy furniture, which are neither distinguished by sublimity

nor beauty, and are estimated only by the labour required to produce what is

trifling or worthless, and are consequently nothing more than obtrusive proofs

of the wealth of the immediate possessor. The motive for the production of

such toys is mercenary, and the admiration of them childish or servile. That

which pleases merely from its novelty, or because it was never seen before,

cannot be expected to please twice: that which is remarkable for the difficulty

or costliness of the execution can be interesting to no one but the [290] maker

or owner. A shell, however rarely to be met with, however highly wrought or

quaintly embellished, can only flatter the sense of curiosity for a moment

in a number of persons, or the feeling of vanity for a greater length of time

in a single person. There are better things than this (we will be bold to say)

in the world both of nature and art – things of universal and lasting

interest, things that appeal to the imagination and the affections. The village-bell

that rings out its sad or merry tidings to old men and maidens, to children

and matrons, goes to the heart, because it is a sound significant of weal or

woe to all, and has borne no uninteresting intelligence to you, to me, and

to thousands more who have heard it perhaps for centuries. There is a sentiment

in it. The face of a Madonna (if equal to the subject) has also a sentiment

in it, "whose price is above rubies." It is a shrine, a consecrated

source of high and pure feeling, a well-head of lovely expression, at which

the soul drinks and is refreshed, age after age. The mind converses with the

mind, or with that nature which, from long and daily intimacy, has become a

sort of second self to it: but what sentiment lies hid in a piece of porcelain?

What soul can you look for in a gilded cabinet or a marble slab? Is it possible

there can be any thing like a feeling of littleness or jealousy in this proneness

to a merely ornamental taste, that, from not sympathising with the [291] higher,

and more expansive emanations of thought, shrinks from their display with conscious

weakness and inferiority? If it were an apprehension of an invidious comparison

between the proprietor and the author of any signal work of genius, which the

former did not covet, one would think he must be at least equally mortified

at sinking to a level in taste and pursuits with the maker of a Dutch toy.

Mr. Beckford, however, has always had the credit of the highest taste in works

of art as well as in vertù. As the showman in Goldsmith's comedy declares

that "his bear dances to none but the genteelest of tunes – Water

parted from the Sea, The Minuet in Ariadne;" – so it was supposed

that this celebrated collector's money went for none but the finest Claudes

and the choicest specimens of some rare Italian master. The two Claudes are

gone. It is as well – they must have felt a little out of their place

here – they are kept in countenance, where they are, by the very best

company!

We once happened to have the pleasure of seeing Mr. Beckford in the Great Gallery

of the Louvre – he was very plainly dressed in a loose great coat, and

looked somewhat pale and thin – but what brought the circumstance to

our minds was that we were told on this occasion one of those thumping matter-of-fact

lies which are pretty common to other Frenchmen besides Gascons – viz.,

That he had offered the First [292] Consul no less a sum than two hundred thousand

guineas for the purchase of the St. Peter. Martyr. Would that he had! and that

Napoleon had taken him at his word! – which we think not unlikely. With

two hundred thousand guineas he might have taken some almost impregnable fortress. "Magdeburg," said

Buonaparte, "is worth a hundred queens:" and he would have thought

such another stronghold worth at least one Saint. As it is, what an opportunity

have we lost of giving the public an account of this picture! Yet why not describe

it, as we see it still "in our minds eye," standing on the floor

of the Tuileries, with none of its brightness impaired, through the long perspective

of waning years? There it stands, and will for ever stand in our imagination,

with the dark, scowling, terrific face of the murdered monk looking up to his

assassin, the horror-struck features of the flying priest, and the skirts of

his vest waving in the wind, the shattered branches of the autumnal trees that

feel the coming gale, with that cold convent spire rising in the distance amidst

the sapphire hills and golden sky – and overhead are seen the cherubim

bringing with rosy fingers the crown of martyrdom; and (such is the feeling

of truth, the soul of faith in the picture) you hear floating near, in dim

harmonies, the pealing anthem, and the heavenly choir! Surely, the St. Peter

Martyr surpasses all Titian's other works, as he himself did all other painters.

Had [293] this picture been transferred to the present collection (or any picture

like it) what a trail of glory would it have left behind it! for what a length

of way would it have haunted the imagination! how often should we have wished

to revisit it, and how fondly would the eye have turned back to the stately

tower of Fonthill Abbey, that from the western horizon gives the setting sun

to other climes, as the beacon and guide to the knowledge and the love of high

Art!

The Duke of Wellington, it is, said, has declared Fonthill to be "the

finest thing in Europe." If so, it is since the dispersion of the Louvre.

It is also said that the King is to visit it. We do not mean to say it is not

a fit place for the King to visit, or for the Duke to praise: but we know this,

that it is a very bad one for us to describe. The father of Mr. Christie was

supposed to be "equally great on a ribbon or a Raphael." This is

unfortunately not our case. We are not "great" at all, but least

of all in little things. We have tried in various ways: we can make nothing

of it. Look here – this is the Catalogue. Now what can we say (who are

not auctioneers' but critics) to

Six Japan heron-pattern embossed dishes; or,

Twelve burnt-in dishes in compartments; or,

Sixteen ditto enamelled with insects and birds; or,

Seven embossed soup-plates, with plants and rich borders ; or,

[294] Nine chocolate cups and saucers of egg-shell China, blue lotus pattern;

or,

Two butter pots on feet, and a bason, cover, and stand, of Japan; or,

Two basons and covers, sea-green mandarin; or,

A very rare specimen of the basket-work Japan, ornamented with flowers in relief,

of the finest kind, the inside gilt, from the Ragland Museum; or,

Two fine enamelled dishes scolloped; or,

Two blue bottles and two red and gold cups - extra fine; or,

A very curious egg-shell lanthern; or,

Two very rare Japan cups mounted as milk buckets, with silver rims, gilt and

chased; or,

Two matchless Japan dishes; or,

A very singular tray, the ground of a curious wood artificially waved with

storks in various attitudes on the shore, mosaic border, and aventurine back;

or,

Two extremely rare bottles with chimæras and plants, mounted in silver

gilt; or,

Twenty-four fine OLD SEVE dessert plates; or,

Two precious enamelled bowl dishes, with silver handles; –

Or, to stick to the capital letters in this Paradise of Dainty Devices, lest

we should be suspected of singling out the meanest articles, we will just transcribe

a few of them, for the satisfaction of the curious reader :

A RICH and HIGHLY ORNAMENTED CASKET of the very rare gold JAPAN, completely

covered with figures.

An ORIENTAL SCULPTURED TASSA OF LAPIS LAZULI, mounted in silver gilt, and set

with lapis lazuli intaglios. From the Garde Meuble of the late King of France.

A PERSIAN JAD VASE and COVER, inlaid with flowers and ornaments composed of

oriental rubies and emeralds, on stems of fine gold.

[295] A LARGE OVAL ENGRAVED ROCK CRYSTAL CUP, with the figure of a Syren, carved

from the block and embracing a part of the vessel with her wings, so as to

form a handle; from the ROYAL COLLECTION OF FRANCE.

An OVAL CUP and COVER OF ORIENTAL MAMILATTED AGATE, richly marked in arborescent

mocoa, elaborately chased and engraved in a very superior manner. An unique

article.

Shall we go on with this fooling? We cannot. The reader must be tired of such

an uninteresting account of empty jars and caskets – it reads so like

Della Cruscan poetry. They are not even Nugæ Canoræ. The pictures

are much in the same mimminèe-pimminèe taste. For instance, in

the first and second days' sale we meet with the following: –

A high-finished miniature drawing of a Holy Family, and a portrait: one of

those with which the patents of the Venetian nobility were usually embellished.

A small landscape, by Brueughel.

A small miniature painting after Titian, by Stella.

A curious painting, by Peter Peters Brueughel, the conflagration of Troy – a

choice specimen of this scarce master.

A picture by Franks, representing the temptation of St. Anthony.

A picture by old Brueughel, representing a fête – a singular specimen

of his first manner.

Lucas Cranach – The Madonna and Child – highly finished.

A crucifixion, painted upon a gold ground, by Andrea Orcagna, a rare and early

specimen of Italic art. From the Campo Santo di Pisa.

A lady's portrait, by Cosway.

Netecher – a lady seated, playing on the harpsichord, &c.

Who cares any thing about such frippery, [296] time out of mind the stale ornaments

of a pawn-broker's shop; or about old Brueughel, or Stella, or Franks, or Lucas

Cranach, or Netecher, or Cosway? – But at that last name we pause, and

must be excused if we consecrate to him a petit souvenir in our best manner:

for he was Fancy's child. All other collectors are fools to him: they go about

with painful anxiety to find out the realities: – he said he had them – and

in a moment made them of the breath of his nostrils and the fumes of a lively

imagination. His was the crucifix that Abelard prayed to – the original

manuscript of the Rape of the Lock – the dagger with which Felton stabbed

the Duke of Buckingham – the first finished sketch of the Jocunda – Titian's

large colossal portrait of Peter Aretine – a mummy of some particular

Egyptian king. Were the articles authentic? – no matter – his faith

in them was true. What a fairy palace was his of specimens of art, antiquarianism,

and vertù, jumbled all together in the richest disorder, dusty, shadowy,

obscure, with much left to the imagination (how different from the finical,

polished, petty, perfect, modernised air of Fonthill!) and with copies of the

old masters, cracked and damaged, which he touched and retouched with his own

hand, and yet swore they were the genuine, the pure originals! He was gifted

with a second-sight in such matters: he believed whatever was incredible. Happy

mortal! Fancy bore sway in him, and so vivid [297] were his impressions that

they included the reality in them. The agreeable and the true with him were

one. He believed in Swedenborgianism – he believed in animal magnetism – he

had conversed with more than one person of the Trinity – he could talk

with his lady at Mantua through some fine Vehicle of sense, as we speak to

a servant down stairs through an ear-pipe. – Richard Cosway was not the

man to flinch from an ideal proposition, Once, at an Academy dinner, when some

question was made, whether the story of Lambert's leap was true, he started

up, and said it was, for he was the man that performed it; – he once

assured us, that the knee-pan of James I. at Whitehall was nine feet across

(he had measured it in concert with Mr. Cipriani); he could, read in the book

of Revelations without spectacles, and foretold the return of Buonaparte from

Elba and from St. Helena. His wife, the most lady-like of English-women, being

asked, in Paris, what sort of a man her husband was, answered, Toujours riant,

toujours gai. This was true. He must have been of French extraction. His soul

had the life of a bird; and such was the jauntiness of his air and manner that,

to see him sit to have his half-boots laced on, you would fancy (with the help

of a figure) that, instead of a little withered elderly gentleman, it was Venus

attired by the Graces. His miniatures were not fashionable – they were

fashion itself. When more [298] than ninety, he retired from his profession,

and used to hold up the palsied right hand that had painted lords and ladies

for upwards of sixty years, and smiled, with unabated good humour, at the vanity

of human wishes. Take him with all his faults or follies, "we scarce shall

look upon his like again!"

After speaking of him, we are ashamed to go back to Fonthill, lest one drop

of gall should fall from our pen. No, for the rest of our way, we will dip

it in the milk of human kindness, and deliver all with charity. There are four

or five very curious cabinets – a triple jewel cabinet of opaque, with

panels of transparent amber, dazzles the eye like a temple of the New Jerusalem – the

Nautilus's shell, with the triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite, is elegant, and

the table on which it stands superb – the cups, vases, and sculptures,

by Cellini, Berg, and John of Bologna, are as admirable as they are rare – the

Berghem (a sea-port) is a fair specimen of that master – the Poulterer's

Shop, by G. Douw, is passable – there are some middling Bassans – the

Sibylla Libyca, of L. Caracci, is in the grand style of composition – there

is a good copy of a head by Parmegiano – the painted windows in the centre

of the Abbey have a surprising effect – the form of the building (which

was raised by torch-light) is fantastical, to say the least – and the

grounds, which are extensive and fine from situation, are laid out with the

hand of a master. A quantity [299] of coot, teal, and wild fowl sport in a

crystal stream that winds along the park; and their dark brown coats, seen

in the green shadows of the water, have a most picturesque effect. Upon the

whole, if we were not much pleased by our excursion to Fonthill, we were very

little disappointed; and the place altogether is consistent and characteristic.